Beyond “Zombie Formalism” – Painting After The End Of Painting (Iwo Zmyślony)

|

Rather than initiating the death of painting, as was expected, photography and other media of mechanical reproduction have been like a vampire’s kiss that makes painting immortal. Painting is the enthralled before the cold eye of mechanical reproduction and can stare back in the same way. -David Reed (2003)

Any return to painting taking place now?

In a way. At least it is one of current tendencies. Return to painting, return to sculpture, return to object. My guess is it is all about trade issues. Objects are way easier to store and sell than installation art or performance.

Michel Houellebecq, “The Map and the Territory” (2010)

What is the current situation of painting? Can any innovative trends be discerned? Questions of this kind must be overwhelming, because they guide us into an endless mire. It would be difficult to say how to start and where to look for dependable answers. Should one rely on online rankings along the lines of “25 Most Interesting” or “Most Promising Artists”? Perhaps one should opt for books, such as Painting Now, Painting Today or 100 Painters of Tomorrow?

Is there anyone at all who writes history of painting nowadays? Publishers? Internet users? Private collectors? Art institutions? Or perhaps painting has no history anymore? Pictures exist today all at once after all, accessible by means of one click, in the timeless, spaceless void of the internet. It may be that the only thing we have is the infinite multitude of links, simulacra, hypertext and imagery thrown up by a search engine?

What if one took the plunge, and immersed themselves in the endless procession of panels, exhibitions, competitions, biennials and art fairs? What criteria should one use then? What determines the quality of painting today? Market value? Reputation of the author? Prestige of the exhibiting institution? The name of the curator?

What is the point of talking about technical prowess or innovativeness? Considering the tremendous bulk of painterly output, is it still possible to establish some general criteria? Perhaps quite the opposite is the case – all criteria are inevitably to be applied only locally? If so, on whom are they dependent, who holds power and authority over them?

One thing is certain; the quantity of painting is increasing at a tremendous pace. The question is, what does it attest to? May it be that the key to understand that phenomenon lies in the cynical conclusion of Houellebecq’s? To put it bluntly, is contemporary painting geared exclusively towards producing decorative material and investment assets? Has painting still any vital issues which could be addressed and creatively resolved? Is it still a domain of important debates and consequential disputes?

When posing all those questions I cannot shake off the persistent impression I was left with upon seeing an exhibition of Jeff Koons’s in one of the NY galleries of Larry Gagosian (Gazing Ball Paintings, 9.11-23.12.2015, 522 West 21st Street). I remember I had gone there guided by a perverse need to see something truly cynical, something I do not believe at all, but which I had read and heard so much about. After all, an opportunity of that kind does not happen every day.

The show consisted of several superior-quality painterly reproductions, painted by hand (!), which were hung freely in the sterile exhibition space. Koons had paintings of the great masters, including Manet, Courbet, Turner, El Greco, Rubens, Titian or Rafael, copied to very compact dimensions, differing slightly in scale from the originals. In front of each picture, he placed a large, shiny blueish ball of luminescent glass, affixed to an aluminium slate. Hence the title: Gazing Ball Paintings.

I can perfectly recall the frustration. Frustration with what, though? Precisely with nothing. With the ostentatious emptiness. With the ostentation of banality which went far beyond my expectations. Why then, ten months later, Koons returns with irritating tenacity when I am writing a text about painting? Within that space of time, I have seen very much indeed. In the very same New York City, there was the brilliant show of Jim Shaw’s at the New Museum, splendid paintings by Martin Wong at the Bronx Museum, monumental retrospectives of Burri at the Guggenheim, Frank Stella’s at Whitney or Picasso’s at the MoMA, not to mention several smaller galleries. However, all this comes back only when I scroll down my own Instagram feed.

A view. An ineffaceable view. To create a picture which surpasses all other pictures – is this not the challenge for a contemporary painter? Does not art consist in creating something visible for a change, today, in times of the ‘The Hypertrophy of the Visual’, in the deluge of hoardings, banners, digital interfaces, logotypes, icons, news, ads and porn? To create a signal which would arrest our attention, fatigued and distracted by the noise of thousand other signals?

The above gesture performed by Koons may readily be treated as a (post)conceptual play with the status of painting and the painterly medium or, alternatively, neo-Duchamp-esque (critical? why not?) reflection on tradition, in the face of deepening crisis of representation, in the post-television and post-internet era. The artist himself declares that he sees the project to be a “contemplative, philosophical reflection”, a “metaphysical dialogue” with “the DNA of culture” as well as, obviously so, the essence of humanity condensed in art. The artist is cited by M.H. Miller in an essay in ARTnews.

The perverse potency of Koons’s work consists in fact in something utterly opposite. While evoking all those textbook interpretations, it continues to elude them, remaining what it is, a spectacular cliché, a copy of great painting, which is semantically naked, stripped of all meaning, reduced to a state of ostentatious emptiness .

This may be the reason why one can hardly ignore Koons when thinking about contemporary art. Perhaps he externalizes the internalized? Unceremoniously, he demonstrates what the art world prefers to repress: the inevitable derivative nature of most artistic output, its conceptual vacuity, shamefacedly left unspoken (or guessed at).

Koons’s exhibitions represents and extreme case, thus exposing the contemporary condition of painting in extreme terms. One the one hand everything has already been invented, so one cannot expect innovative solutions. On the other, demand for new painting does not abate, but evidently grows. Why not repeat history openly, then? Why not channel the entire energy to a spectacle?

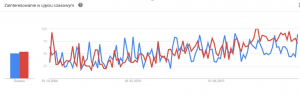

One of the symptoms of the schizophrenic condition of painting are the recurring debates concerning its demise. Over the course of the last decade, the query was made 54 times per month, on average, occurring a little more frequently than the topic of the medium’s comeback. Interestingly enough, the frequency of searchers fluctuated in particular months. For instance, whereas the “death of painting” clearly predominated in May 2016 (at the ratio of 95:44), the proportion was reversed in September, with 89:70 in favour of the “return of painting”6. At this moment (late September) the search for “painting is dead” turns up 147,000 hits, while “painting is back” yields 224,000 results. The question is, what does it signify? Quite certainly, something is afoot.

*interest over time

“Death of Painting” is one of the leitmotifs of modern culture, closely associated with the idea of the avant-garde. From the mid-19th century onwards, painting would die many times, most often due to loss of historical function (with the function of producing visions of history at the forefront) to the successive technologies of mechanical reproduction: photography, printed imagery, cinema and television. Still, technology, or to be more precise the attempts to tame it brought about revivals of painting, which is splendidly exemplified by Impressionism, Futurism or Pop art.

An alternative path along which painting evolved was exploiting its own ontology, the element which distinguishes it from mechanical forms of representation and which makes it unique with respect to another media. At least, this is how it was viewed by the then criticism and how the later history of art envisaged it. Thus, one can account for the development of abstraction as well as expressionist and surrealist currents. The former delved into the formal-material and structural-functional premises of a painting, while the latter explored the forces of the painterly gesture and subjective visions.

One thing both of those approaches shared was teleologism, an orientation towards certain ideal goals which on the one hand determined and defined the very notion of painting, while on the other set out the criteria for progress, which materialized in the artistic practice of successive generations. Given such a viewpoint, painting had a history, being a sequence of breakthroughs and watersheds, new schools and currents which followed a linear alignment along the temporal axis.

This thoroughly Hegelian vision presupposed the existence of a certain cut-off point, an ideal horizon beyond which painting would not be able to venture. Per the adherents (with Arthur Danto in the lead) such an end had already come, more or less five decades ago, with the birth of conceptualism, when Ad Reinhardt was making the last “black paintings”, and Donald Judd created the first “specific objects”.

In his concept of the ‘end of art’ Danto draws upon the views of Clement Greenberg and his idea of ‘medium specificity’, which he interprets as a “Kantian question about the capacities of painting itself”. The assertion was that painting had certain immanent traits, such as planarity, materiality of paint or brush stroke, which were revealed one after another by successive generations of painter, beginning with Manet, and ending with Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman, according to Danto in After the End of Art. Similar views are expressed by Hans Belting in Das Ende der Kunstgeschichte. Eine Revision nach zehn Jahren.

At the time, painting faced a choice: either to repeat history, revisit old ideas and devour its own tail or to extend the conditions of its self-determination. The former found its reflection in the panoply continually developed post- modernist strategy. The latter gave rise to the work of such artists as Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, Robert Ryman, Daniel Buren or representatives of Op art.

In these circumstances, history ceased to be the (sole) source of criteria for painting. A new reservoir was found in contemporaneity, in the abundance of discourses, contexts and strategies (popular culture, feminism, post-colonialism, trauma theories etc.) rationed by art institutions. The poignant sense of exhaustion and disorientation was aptly voiced in an essay by Douglas Crimp, who proclaimed the end of the medium on the pages of October. Shortly afterwards a new factor came into play, changing the rules of the painting game.

The boom on the art market meant a new set of cards had been dealt, in the shape of increased demand for paintings. One of the responses was the resurrection of expressionism in the works of Polke, Kiefer, Baselitz, Schnabl, Basquiat or the Italian trans-avant-garde. Curiously enough, nobody called them ‘zombies’.

The latter designation is there today, in the new reality of Facebook, Instagram and cheap airlines, having emerged with the outpouring of styles that history of art had long ago buried. It has been called “‘formalism’ because this art involves a straightforward, reductive, essentialist method of making a painting (…), and ‘Zombie’ because it brings back to life the discarded aesthetics of Clement Greenberg”, as Walter Robinson writes in Artspace.

The very word ‘zombie’ is a catchy one, it is cool because it tastes of the macabre but can be subversive as well. This is due to the fact that it suggests certain traits and qualities of painting, as well as an approach – shorn of authenticity, dead, zombiastic. The accusations are hurled chiefly at dealers and buyers, but ricochets do reach the authors as well. Jerry Saltz is probably the one to sum up the situation most brutally, as he stated point- blank that the only reason for the extinct styles to make a comeback is the demand on the art market. Only this can explain the ubiquity of ‘zombies’ on various fairs, from Hong Kong to Miami and Berlin, as Saltz writes in Vulture.

Saltz and critics thinking alike not only point out the derivativeness and conformity of hundreds of paintings which wave the banner of new abstraction, but also denounce their authors’ opportunism, in that they turn out products catered to the need and expectations of private collectors, particularly the novices who still lose their bearings in the labyrinth of history of art, but who easily succumb to the suggestions of the art world and seek quick capital gains, according to Howard Hurst. Indeed, auction ratings of artists such as Joe Bradley, Jacob Kassay, Parker Ito, Oscar Murillo or Lucien Smith are truly impressive.

Seven or eight years ago their works would have fetched several hundred dollars, today they are worth tens, even hundreds of thousands. At least, this is what one can infer from the rankings published at ArtRank.com (It should be noted that in mid-September 2016 the market registered a substantial drop, notes Karen Archey in e-flux.

Thus ‘zombie’ stands for cynicism, cold calculation, dispassionate distance to creating art and its promotion while bypassing traditional art institutions, and utilizing online platforms and new technologies instead. The situation is thus assessed by Daniel Palmer, a critic who with palpable horror describes his visit to the studio of a young artist considered a representative of the current scene. It would be worthwhile to compare his essay with the theses of a much-debated interview given two and a half years previously by a leading publicist of artists from that circle.

This sort of oeuvre looks brilliant when posted on social media, promising its purchasers high rates of return and a membership in the circles of young global elite, where movie-world celebrities and creative IT geeks are the cream of the crop. Works of that kind are not made with museum collection and cavernous exhibition hall in mind. Instead, their compact dimensions look marvellous on a tablet screen and in the minimalist interiors of modern penthouses and corporate offices.

Nevertheless, even ‘zombies’ have their enthusiasts, who argue that in critical discourse one should leave the contexts of market mechanisms and Hegelian history of art aside. They do not perceive the work they discuss as a return of style “from beyond the grave” but envisage it as a redefinition of the very idea of painting, given the broader spectrum of transformations in contemporary visual culture, especially considering what the internet and the new media have done to our perception of an image.

“Many of these artists don’t have a background in painting, and nor do they need to”, says Alex Bacon, one of the enthusiastic researchers of the new current to which he refers as ‘new abstraction’. “[…] after all a shallow thing that is hung parallel to the wall has as much to do with digital technology—those shallow objects like tablets, smartphones and flat-screen televisions that serve as vehicles for the delivery of any range of content and imagery—today as it does with painting’s art historical legacy. For artists that are trying to address questions of perception and materials, and even of space, something like painting becomes a useful mode to adopt. […] It is a lens, a frame, a proposition for something that poses as, adopts the form of, etc., a painting”.

A similar approach was adopted by Laura Hoptman, experienced curator at the MoMA. The exhibition she organized, entitled Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World (December 2014 – April 2015) was the first show of contemporary painting in that prestigious venue in over 30 years. Presenting the works of seventeen artists, she would sometimes use the term ‘zombie’, clearly dissociating herself from it at the same time. For her, the key notion was the title “atemporalness” of paintings. It should be noted that similar premises had been adopted by the creators of the monumental Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age, an exhibition held at the same time at thee Museum Brandhorst in Munich. The exposition comprised 230 works of 107 artists and an extensive catalogue, which was published as well.

Everything seems to indicate that we are living in interesting times for painting. They may be even more interesting than in mid-20th century, when progress and innovation were defined through the history of the medium. This is very much in keeping with the conjectures of Danto, as he prophesied the coming of a new age of artistic plurality, in which nothing would be constrained by a binding aesthetic doctrine. That does not mean lack of any criteria whatsoever, but merely indicates that none of the criteria are final and all can be negotiated.

Iwo ZmyślonyIwo Zmyślony is an art critic, academic lecturer, and independent researcher currently on the faculty at the School of Form, University of Warsaw in Poland. He studied philosophy and history of art at the Catholic University of Lublin, Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and University of Warsaw. He is the author of a dozen of scientific publications on epistemology and methodology of science and few dozens of reviews, essays and interviews in field of art criticism. In 2013 he was awarded the Ph.D. based on a thesis on tacit knowledge and related problems,. He works in the field of interpretation theories, design thinking and history of art of twentieth century and cooperates with major Polish artists and art institutions. Awarded with a dozen of scholarships and grants founded by Polish and international institutions, including the Polish Ministry of Culture (2015), the Polish Ministry of Science (2010-2012), the German Academic Exchange Service, (2005), GFPS (2007) and Ashoka Innovators fort the Public (2001).

Tagged with: abstractionism, Arthur Danto, contemporary art, painting, zombie formalism