Art And Madness, Part 2 (Iwo Zmyślony)

The following is the second installment of a two-part series. The first installment can be found here.

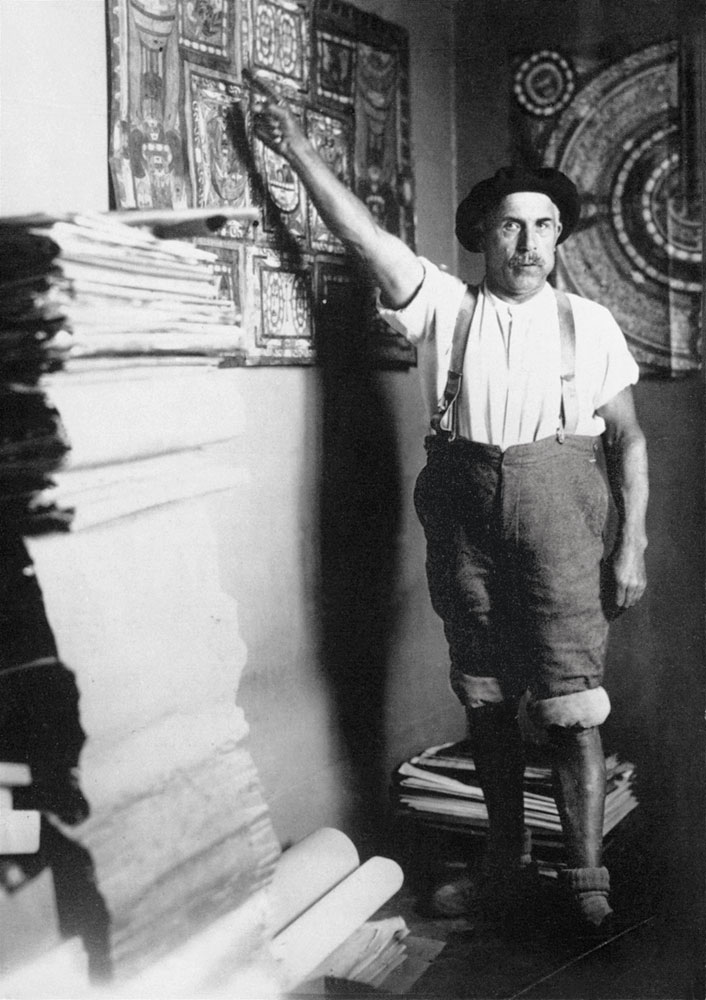

Less than a year prior to the publication of Prinzhorn’s book, another major publication came out titled Madness and Art. The Life and Works of Adolf Wölfli (Ein Geisteskranker als Künstler), where the Swiss psychiatrist Walter Morgenthaler described at length a case of the patient Adolf Wölfli. The man, orphaned as a young boy, growing up in orphanages and foster families, repeatedly physically and mentally abused, was in 1895 institutionalized at the age of thirty in the Waldau Clinic in Bern, and spent there the remainder of his life.

Due to bouts of aggression he was isolated and diagnosed with a psychosis with hallucinations. A few years later, suddenly he started to demonstrate a unique talent for the arts and would painstakingly fill sheets of paper with text and drawings, initially with pencils and later with color crayons supplied by the hospital staff.

In 1908 Wölfli began to create in this way a monumental work: a fictitious autobiography he elaborated on continuously until his death in 1930. For this work, he created a full universe of places and people, imaginary lands that are breathtaking due to their numerous forms and details. The fantastic narrative is accompanied by intricate, decorative illustrations, not infrequently with a covert musical notation. The work runs to over 25,000 pages and is currently housed in the Bern Museum of Fine Arts, where a foundation named after him operates. André Breton considered this collection as one of the three major legacies of the twentieth century.

According to Morgenthaler, Wölfli’s oeuvre provides a more extensive insight into the essence of artistic creation than the works of ordinary artists. It is to develop in a dialectic tension between two contradictory forces: “on the one hand we deal with some unbridled drive, something overpowering which tries to break free from time-space in its pursuit of fullness. Morganthaler notes:

There is some violent intensity and power of symbol here, an urge towards absolute freedom, an urge which undermines and brutally maims all natural forms; there is disquieting passion and inner quivering; a desire to cram all into a single small piece of paper; to express everything in one idea. This is something both mystical and demoniacal. There is, however a force that harnesses all that and imposes obedience, outer calm and distance; it allows a cool calculation of fact and even indifference. There is some discipline that regulates all that, reaching the limits of monotony, formalization and petrification.(Arnheim, 116)

To define Wölfli’s work as to its form, apart from the evident horror vacui and disrespect for the principles of perspective, Morgenthaler indicated the compulsive repetition of motifs, an ambivalent relation between the background and the figure as well as a predilection for shapes that can be interpreted at least in two ways.

Analogous features in the art of the mentally ill were indicated also by other scholars interested in this art. The aforementioned Emil Kraepelin pointed out the notorious combination in these works of words and images and the treatment of text as ornament. In turn, Prinzhorn, like Morgenthaler, stressed the dialectic tension between the “representation urge” and the obsessive tendency to use patterns and ornaments.

Arnheim explains these properties by focusing, characteristic of modernity, on the purely material properties of the medium: the plane and two dimensions of a paper sheet or canvas and the artistic consistency of paint, as well as other techniques. Gesture, patch and colour moreover help directly express powerful affective inner states and therefore objectify them and distance to them.

In Breton’s circles in Paris Prinzhorn’s publication was quite obviously received with great enthusiasm, since the Surrealists treated madness as a promise of liberation from culture-imposed standards and prohibitions, seen after Freud as the source of suffering. Their new art was supposed to provide an antidote to the traumatic dictatorship of mind and custom, to undermine the established structures of “common sense” which stifle the libidinal energies accumulated in the human being.

Hence the predilection for text and image where reason is totally helpless (or, to paraphrase the famous sentence from Comte de Lautréamont’s The Songs of Maldoror, which are as beautiful as a chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an autopsy table).

First and foremost, they were attracted to dreams which according to Freud harbor suppressed unfulfilled desires, traumatic experiences and fears. They do not appear in their primary form but rather “encrypted” by the work of the subconscious which, stripped of the control of reason, reverses their senses and destroys logical order. That is why dreams are visual puzzles with a hypnotizing form. Breton saw this kind of art e.g. in the painting of Max Ernst, Georgio de Chirico, Salvador Dali, and Marc Chagall, as well as in that by Paolo Uccella, Giuseppe Arcimboldo and Hieronymus Bosch.

In search of analogous effects, the Surrealists started to apply a variety of techniques. This was meant to liberate the creative process from the control of the mind and consciousness. One of them was, naturally, automatic drawing, or spontaneous and unmonitored drawing of forms and shapes which revealed purely emotional tensions. Other basic techniques included assemblage, collage and photomontage, previously used by the Dadaists. They allow an inclusion in a single composition of logically incongruous objects, sometimes with totally opposite properties.

André Masson was a virtuoso of automatism in painting. When a wartime émigré in New York, he supposedly inspired Jackson Pollock. The techniques of photomontage, assemblage and collage were used, in turn, by e.g. Max Ernst. Like Paul Klee, he encountered the art of the mentally ill prior to World War I, at Bonn University, where apart from philosophy and art history he studied psychiatry and psychology.

These inspirations can be found in the famous “Master’s Bedroom”, a paranoid collage made around 1920 where the claustrophobic space is filled with single animal figures, torn out of their natural context and located in a bizarre and tense order. The very technique of execution is important. It consists in applying a layer of gouache onto a found object (teaching table), followed by its abrasion in a few selected places to bring out the images hidden below. This represents the mechanics of the processes of creating memories and eroding memory.

Chance was another attractive strategy employed by the Surrealists; its use guaranteed a lack of the interference of reason or conscious intent in the creative process. Its operation is best illustrated by Breton’s anecdote. He once bought a rather strange object at a flea market. It was a long wooden spoon with a miniature shoe carved at its end. When he brought it home, he suddenly realized that he’d found an object whose production had been vainly sought by Alberto Giacometti, who’d had for a long time been toying with an idea of a shoe-shaped ashtray. A conscious desire was suppressed, however, only to return as a subconscious motif of his accidental choice.

“Surrealism”, Breton wrote in the first manifesto of 1924, “is pure mental automatism used to express in word, writing or another way the actual operation of thoughts. This is a dictation of thoughts in the absence of all control of reason, beyond all aesthetic or moral tests”. And, as he declared in Surrealism and Painting in 1928:

“The eye exists in the wild … I cannot treat a painting differently than as a window and immediately a question arises about what this window overlooks; in other words, is the view from where I am beautiful. I love most what stretches before me until the gaze is lost”.

The work of Prinzhorn and Morgenthaler attracted the interest of one more person, a little-known wine merchant, art collector and wannabe painter. Only many years later, in the middle of World War II, did he decide to leave his family business and dedicate himself to visual arts. He travelled psychiatric hospitals for inspiration. Today he is seen, next to Fautrier and Wols, as one of the leading precursors of European Art Informel. His name is Jean Dubuffet.

In 1948, along with André Breton, André Gide and Michel Tapié, he set up the Art Brut Society (La Compagnie de l’Art Brut), whose objective was to hold exhibitions of mental patients’ work. The first such show took place the following year in the prestigious Drouin René Gallery in Paris, gathering over two hundred works by close to sixty artists. In the mid-1960s Dubuffet began to issue a specialist periodical L’Art Brut and systematically enlarge his own collection. Ten years later he decided to donate it to the city of Lausanne and made available to the public. Today they number close to 60,000 objects, 700 of which are permanently exhibited.

Dubuffet wrote in his essay “Make Way for Incivism”:

“The works were created by solitude as well as by pure and deeply genuine outbursts of creative fulfilment, not interrupted by the desire to compete, being recognized or advancing socially. It is because of this; they are all the more precious than the work of professional artists. It is sufficient to be in contact with these testimonies to elation and frenzy, experienced so profoundly and so intensively by their authors to observe that in comparison to them all official art seems an empty game, a pitiful masquerade”(36).

In his “Notes and Comments” from The New Yorker in June, 1973, Dubuffet added: “For myself madness is something completely normal. It is rather normal people who are mentally ill. Being normal means an absence of imagination and creativity” (27).

A question reappears, then: how shall we look at all that? How do we get closer to it? How to leave one’s own eye and enter someone else’s head? What is the difference between what unites us and what divides us?

Michel Foucault’s “History of Madness” (Folie et déraison. Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique) was first published in 1961. This phenomenon was shown here as a historical construct, a unique invention of modern culture which, narrowing down the notion of reason, rejected the earlier, medieval and renaissance, treatment of madness as a source of wisdom, the way the mind experiences the mysteries hidden from it.

Foucault saw the breakthrough in the mid-17th c., when Descartes defined reason as a realm of self- conscious and logical cognition (clara et distincta cognitio), while madness was a separated un- reason, its negative. It was then that the Salpêtrière Hospital was opened on the outskirts of Paris, a place of isolating social aliens, i.e. vagrants, prostitutes and homosexuals, on a par with the mentally ill. Thus, madness, earlier connected with reason, started to be perceived as something separate and external to reason, something to be isolated and on no account communicated with.

The very mental illness is, according to Foucault, a still later construct, the product of the Protestant work ethic and the transformations of the nineteenth century. It was then, along with the development of industry, overpopulation of cities and growth in the importance of the middle class, that the cheap labour demand grew. Thus, people unable to work were seen as amoral (socially useless). Treating madness as an illness, i.e. something that can be treated, contained a promise of restoring the social equilibrium and at the same time justified the development of psychiatry and its practices of discipline and coercion (primarily lobotomy and electric shocks).

Foucault’s views, although widely censured, were emblematic for anti -psychiatry. This ideological movement of the 1960s not only questioned the scientific status of psychiatry but also considered it first and foremost as an institutionalised form of a repressive control over those individuals who reject the standards of conduct imposed by the statistical majority, thus violating the sense of community and social order.

Anti-psychiatrists argued that mental disorders cannot be treated as objects of research since they are introspective states of consciousness, and as such are not subject to observation; in turn merely speaking about a mental illness assumes some picture of mental health, which can be precisely defined exclusively in economic, political or legal terms. They stressed moreover the hazardous pharmaceuticals used in psychiatry and believed that incapacitation and forced therapy are inadmissible violations of human liberty.

The leading protagonist of the movement, Thomas Szasz, proved in his texts that a mental illness is a kind of myth for constructing our mental comfort. It creates the illusion that the entire reality of human existence is under control. As the images of a “witch” or “possession by demons” were previously used to sanction the social authority of the church, the image of a “mental illness” serves today the sanctioning of the authority of all kinds of institutions which derive tangible profits e.g. from the sale of pharmacological products and the provision of therapeutic services.

While Szasz did not deny that there are all kinds of mental states that are the source of suffering and various dysfunctions, he believed that this kind of experience is an integral part of life. Therefore, instead of fearfully isolating from them, we had better learn to open up to them, treating their manifestations with empathy and respect.

***

Some quotes from Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest offers us some perspective on not only what Szaz is talking about, but the relationship between art and madness.

- “(…) what you want are the reasons for the reasons, and I’m not able to give you those. Not for the others, anyway. For myself? Guilt. Shame. Fear. Self-belittlement. I discovered at an early age that I was – shall we be kind and say different? It’s a better, more general word than the other one. I indulged in certain practices that our society regards as shameful. And I got sick. It wasn’t the practices, I don’t think, it was the feeling that the great, deadly, pointing forefinger of society was pointing at me – and the great voice of millions chanting, ‘Shame. Shame. Shame’. It’s society’s way of dealing with someone different”.

- “I’m different”, McMurphy said. “Why didn’t something like that happen to me? I’ve had people bugging me about one thing or another as far back as I can remember, but that’s not what – but it didn’t drive me crazy”. – “No, you’re right. That’s not what drove you crazy. I wasn’t giving my reason as the sole reason. Though I used to think at one time, a few years ago, my turtleneck years, the society’s chastising was the sole force that drove one along the road to crazy, but you’ve caused me to re-appraise my theory. There’s something else that drives people, strong people like you, my friend, down that road”.

- “Yeah? Not that I’m admitting I’m down that road, but what is this something else?”

- “It is us”. He swept his hand about him in a soft white circle and repeated, “Us”.(265-66)Iwo ZmyślonyIwo Zmyślony is an art critic, academic lecturer, and independent researcher currently on the faculty at the School of Form, University of Warsaw in Poland. He studied philosophy and history of art at the Catholic University of Lublin, Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and University of Warsaw. He is the author of a dozen of scientific publications on epistemology and methodology of science and few dozens of reviews, essays and interviews in field of art criticism. In 2013 he was awarded the Ph.D. based on a thesis on tacit knowledge and related problems,. He works in the field of interpretation theories, design thinking and history of art of twentieth century and cooperates with major Polish artists and art institutions. Awarded with a dozen of scholarships and grants founded by Polish and international institutions, including the Polish Ministry of Culture (2015), the Polish Ministry of Science (2010-2012), the German Academic Exchange Service, (2005), GFPS (2007) and Ashoka Innovators fort the Public (2001).

Tagged with: Andre Breton, André Masson, Hans Prinzhorn, Ken Kesey, madness, Rudolf Arnheim, Surrealism