Art And Madness (Iwo Zmyślony)

The following is the first of a two-part series.

How can we enter someone else’s head? How can we get inside? How can we break through our own, invariably too constricting horizon to reach out to another human being? How can we look at reality from the perspective of another person, to leave our own eye, break free from the ruts of language and overcome stereotypes?

How can we get close to what’s so extremely different, alien, on the opposite side, on the antipode of thinking and at the same time, more than anything, so like myself in everything?

What is the difference between what bring us together and what drives us apart? I am but a reed, the feeblest thing in nature, yet I am a thinking reed. The universe around me absorbs me. Point and infinity. And yet the universe, unlike myself, knows nothing about itself, driven by blind forces. All that takes place within it, must take place. It is I who encompass it with thoughts. To be aware and think – what does it really mean?

How is it to be someone else? Is this at all possible? To be born in another’s head, lock oneself in another’s home, stand in front of another’s wall, cornered, in a labyrinth, in a trap, coiled under someone else’s bed, driven into a room corner. How not to succumb to the illusion that I know something about it, that I am capable of naming it, approximate it, bring it out of the unfathomable depths onto the flat surface of language?

How to remain humble, perceptive and inquisitive? How to resist the irresistible temptation to understand?

***

Language simplifies everything; revealing, it hides away. On the face of it, it points to the essence and yet, imperceptibly, pushes away from the essence. It distracts our attention and attracts attention to itself. Each word in a language denotes only what has existed before. Otherwise, it would be unable to mean many things at the same time. In each word, there is all that has happened and what will happen. Everything and nothing else. Language keeps silent about all it cannot name, all that is unrepeatable or unfathomable. It is language that speaks us, rather than we speak a language.

Meaning is (a) something conscious, (b) something logically coherent and thus (c) can be spoken. Otherwise there is no meaning. All that does not make sense and evades reason disappearing. This is the madness of reason. It represses all that it cannot comprehend and entwine in a network of verbal associations. However, the repressed does not cease to exist but rather starts to work as the unconscious. It is therefore even more present. The limits of my language are the limits of my world. What should not be talked about, should be put on the q.t.

***

When William Utermohlen heard the diagnosis, he had barely turned sixty. Still, he did not stop working. He knew he was racing against time. The series of his last self-portraits (1995-2000) is a striking study of the disintegration of identity. In the first of them the artist’s face is still drawn with a skillful, sweeping line. His gaze is resolute and sharp.

In his eyes the will to survive vies with a sense of awe. However, the following year the gaze fades away and the line gets flaccid. Deformities appear and colors vanish. In time, the tendency intensifies. Finally, the face has no eyes and starts to ooze out of the outlines, transforming into a wobbly doodle. “Alzheimer’s affects the right parietal lobe in particular, which is important for visualizing something internally and then putting it onto a canvas,” Dr. Miller, a neurologist at the University of California who studies artistic creativity in people with brain diseases, says. “The art becomes more abstract, the images are blurrier and vague, more surrealistic. Sometimes there’s use of beautiful, subtle color”

“I believe painting is always about memory,” says Patricia Utermohlen, the artist’s widow, an art history professor. “When Bill got sick, he would work all day, minute after minute, as if he was trying to understand something about himself in this way. He died in 2007, but really he was dead long before that, when the disease meant he was no longer able to draw”.

***

Apparently, at a young age Hans Prinzhorn wanted to be a professional singer. Fate dealt the cards differently, though. He first completed studies in philosophy, psychology and art history, then got married twice and finally started studying medicine to work as a field surgeon during World War I. On coming back from the frontline, he was employed in a psychiatric clinic at Heidelberg University, where he filed the set of patients’ drawings, gathered for diagnostic purposes on the orders of the famous Emil Kraepelin. In 1921 the collection numbered over 4,500 objects made by 435 people from all over the world (mainly from Europe and the United States). The following year Prinzhorn published The Artistry of the Mentally Ill (Bildnerei der Geisteskranken), a comprehensive work which, while not respected by psychiatrists, aroused substantial interest among avant-garde artists.

Prinzhorn’s innovativeness consisted in his treatment of the works of art he studied not only through the prism of psychiatry, but first from the point of view of art, with ah inclusion of the then avant-garde perspective. While he did not use the word “art” (Kunst) in the title, he nevertheless dedicated a lot of time to a description of ten “schizophrenic masters” of his choice, whose works were juxtaposed with those of e.g. van Gogh, James Ensor, Oskar Kokoschka, Alfred Kubin, and Emil Nolde.

Pointing out the similarities, according to Arnheim, he at the same time opposed the popular treatment of artistic genius as a form of madness (114). He approached both kinds of artistic endeavours as equitable forms of expression of the human spirit, a manifestation of the universal “creative urge” (Gestaltungsdrang).

Per Prinzhorn, the urge is used to construct relations with the outside world. He went as far as to write about the bridge linking the “I” of the artist with a separate “I” of the viewer via an invitation to share in the imagination game. Also, he was aware of the fundamental differences between the work of artists and that of the mentally ill:

“the most lonesome artist remains in relation to reality, while a schizophrenic is isolated from humanity and by definition would not and cannot relate to people … In the pictures shown we sense an autistic isolation and terrible solipsism, which go far beyond the limits of psychopathic alienation. It seems, then, that it is here that we discover the essence of the schizophrenic condition” (181-82).

***

Prinzhorn’s comprehensive work soon gained wide acclaim but was hardly the first publication on the artistry of the mentally ill. This issue was addressed in the early nineteenth century by Philippe Pinel, one of the precursors of present-day psychiatry, who described the work by his two patients. In the 1810 book Illustrations of Madness, John Haslam, who worked in the London Bethlehem Hospital, at that time a mental asylum, reproduced drawings by one James Tilly Matthews. The drawings demonstrate with technical precision the mode of operation of an “air loom”, a machine with the aid of which a group of anonymous evil-doers targeting England tortures people and remotely monitors their thoughts.

Like Pinel, Haslam was not interested in the artistic aspect. Along with the precise descriptions of the delusions, they were to prove that Matthews was mentally ill. Today the publication is the first comprehensive study of paranoid schizophrenia.

Moreover, it should be borne in mind that nineteenth-century culture perpetuated the Romantic vision of madness as capable of moving beyond the visible and reaching out to the mysteries which the mind cannot fathom. No wonder that the view, criticized a century later by Prinzhorn, of the affinity of madness and genius gained in popularity at that time.

The first to put it forth was the American physician and social activist Benjamin Rush, who wrote in 1812 that madness may release covert artistic talents in people, “much like the precious and exquisite fossils hidden deep underground unbeknownst to the land’s owners”. A similar belief was espoused by the psychiatrist Paul Meunier, author of The Art of the Mentally Ill (L’Art Chez les Fous), published in 1907 under the pen name of Marcel Réja. He saw mental patients’ art as the prime source of human creativity: “it is the privilege of genius to discover nature and the covert sources of the human spirit, but only a madman may directly confront us with the same experience, clumsily yet purely, in its original form”.

However, the most radical views were presented by Cesare Lombroso, who in his 1864 treatise Genius and Madness (Genio e Follia) equated directly both the eponymous notions. He, too, assumed that madness is capable of making artists also of people who have never held a paintbrush. However, unlike Rush and Meunier, he believed that this state was a pathology, a unique result of the degeneration of the mind, or even a manifestation of regress to a lower evolution level.

As Lombroso wrote, “Geniuses, like the mentally ill, often stutter, are emotionally unstable and influenced by the weather, many of them being in addition left-handed”. To support his statements, he analyzed over a hundred works by patients of psychiatric hospitals. According to Allan Beveridge, he pointed out their unique characteristics, e.g. a meticulous rendition of detail as well as the eccentric and the obscene, monotonous and absurd (596).

A provocative approach to the subject was demonstrated by an anonymous author of an article titled subversively “Mad Artists”, which came out in an 1880 issue of the specialist Journal of Psychological Medicine and Mental Pathology. The title was provocative in that the author consciously selected the work by patients of psychiatric hospitals to demonstrate their similarity in comparison to the work by people without disorders.

The message of the publication was far from trivial as it poses the following question: is there anything like artistry unique for mental patients? What objective grounds can be used to identify it? Can we do it in isolation from the individual authors’ biographies and medical records? If so, to what extent it speaks about the nature of psyche and to what extent it addresses the nature of art?

***

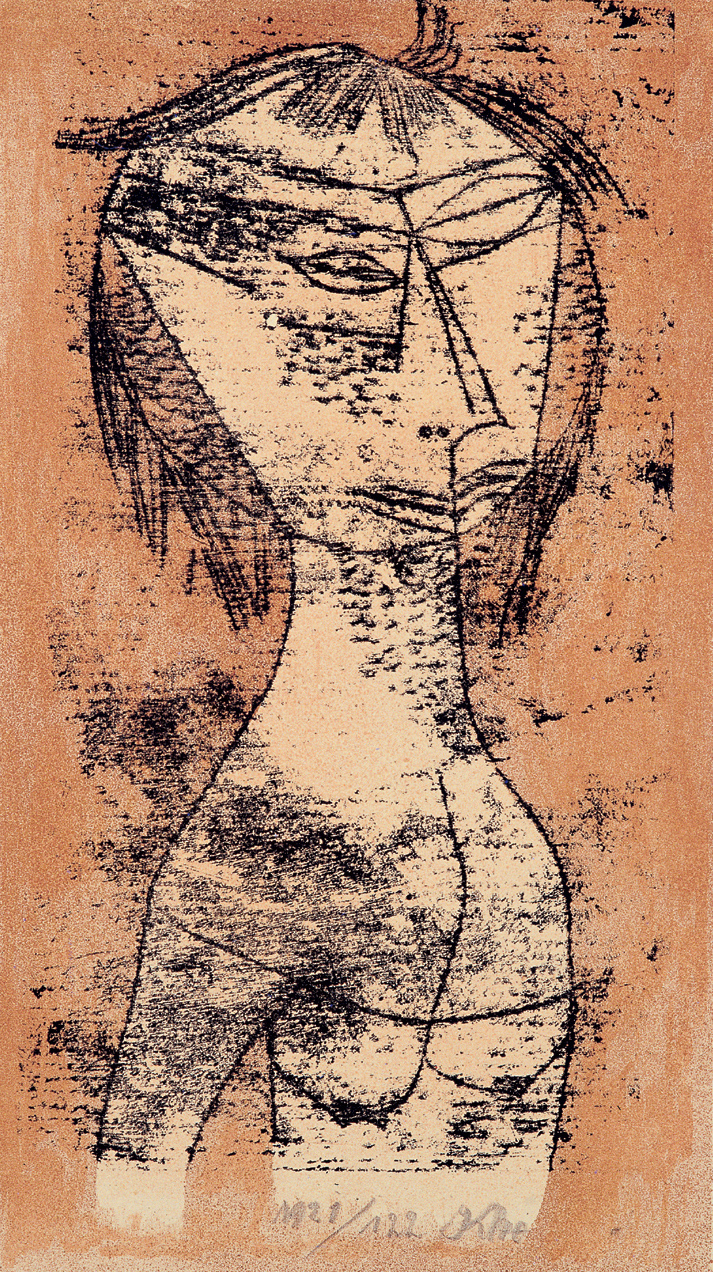

The Painting of the Mentally Ill was, then, a turning point; not only did it usher in a new, artistic approach to the paintings displayed but also opened a new horizon of modern art to totally new areas of inspiration. Prinzhorn’s book was greatly admired by e.g. Paul Klee, at that time a renowned Bauhaus professor, one of the most eminent visionaries of the avant-garde, who consciously used in his own work the artistic solutions addressed in the publication. For instance, he deliberately enlarged the figures’ eyes, transformed their limbs into decorative patterns, and sometimes combined text and image. All of this was meant to assure novel, unprecedented effects of artistic expression.

Klee, in fact, had been inspired by this art slightly earlier, regarding it as a remedy for ossified academic art. “There are primary roots of art, which are easiest to find in the ethnographic collection or a children’s room,” he observed in his journal after the second exhibition of the Blaue Reiter group in 1912. As I wrote in text accompanying Robert Kuśmirowski’s “Palindrom” exhibition in PGS, Sopot (June, 2015),

“Children can do it and this very fact should make us think! The more helpless they are, the more instructive their example and the more we should protect them against falsification. We deal with an analogous phenomenon in the case of works by mental patients, where contemptuous associations with madness or senility are out of place. We should treat all of this as seriously as we can, much more seriously than art museums, if we wish to embark on the great task of a reform”.

“The demented speech of the insane is a higher wisdom since it is something human … Why are we to reject the chance of an insight into the world of free will? Since, it seems to us, we are the masters of madness; since we violate the mentally ill by not allowing them to live per their own ethical standards … Today we must try and overcome our blind approach to mental patients”, wrote Wieland Herzfelde in Die Aktion (1914). The text was quoted in extenso in the catalogue of the mocking show “Degenerate Art” (Entartete Kunst) held by the Nazis in 1937. Reproduced next to it was Paul Klee’s “The Saint of Inner Light” (1921).

Iwo ZmyślonyIwo Zmyślony is an art critic, academic lecturer, and independent researcher currently on the faculty at the School of Form, University of Warsaw in Poland. He studied philosophy and history of art at the Catholic University of Lublin, Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and University of Warsaw. He is the author of a dozen of scientific publications on epistemology and methodology of science and few dozens of reviews, essays and interviews in field of art criticism. In 2013 he was awarded the Ph.D. based on a thesis on tacit knowledge and related problems,. He works in the field of interpretation theories, design thinking and history of art of twentieth century and cooperates with major Polish artists and art institutions. Awarded with a dozen of scholarships and grants founded by Polish and international institutions, including the Polish Ministry of Culture (2015), the Polish Ministry of Science (2010-2012), the German Academic Exchange Service, (2005), GFPS (2007) and Ashoka Innovators fort the Public (2001).

Tagged with: Cesare Lombardo, Hans Prinzhorn, John Haslam, madness, Marcel Reja, Michel Foucault, Paul Meunier, Walter Utermohlen

Comments & Reviews Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.