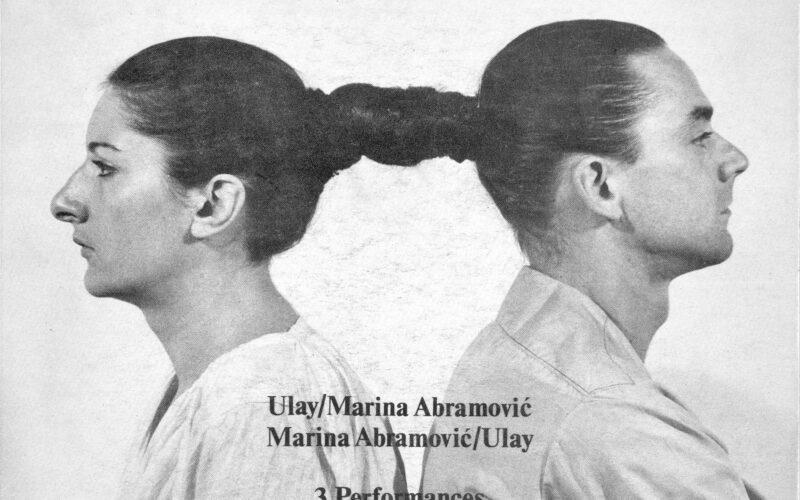

The Phenomenon Of Marina Abramović As Re-enactment Of The Passions Of The Contemporary Elite, Part 2 (Gennady Shkliarevsky)

The following is the second of a two-part series. The first can be found here.

Contemporary artists (including Abramovic) and critics tend to overlook this critical difference between transgression and transcendence. They fail to recognize and, consequently, critically examine this difference. They merely conflate the two and use this unwarranted conflation as the basis for their understanding of the process of creation. Symptomatically, Abramovic who is not shy to engage in extensive theorizing about her works and method does not offer much discussion of the creative process. She accepts the connection between transgression and transcendence as self-evident and leaves it at that.

Like many other contemporary performance artists Abramovic uses transgression—often gratuitously. In her work she inverts familiar notions, values, norms, modes of behavior, etc. She uses fear of exposure and vulnerability, and subjects her viewers to spectacles of self-mutilation, pain, suffering and even a threat of possible death. Abramovic symptomatically entitled one of her shows “The Live and Death of Marina Abramovic.” The thought of how to make a funeral exciting came to Abramovic when she attended the funeral for Susan Sontag.

Her methodology relies on the existing values, norms, and modes of behavior to produce the desired effect. She does not create anything new. The existing forms constantly lurk in the background as the essential referent for her experiments in transgression. Without these referents, her performance simply would not work. They lack the essential autonomy possessed by genuine works of art.

Therefore, in this sense, her work cannot be regarded as a true artistic creation. It is merely an inversion that in its own perverse way merely mimics the original. Such inversion is not dissimilar to what takes place during the development of youngsters when they make the transition from the earlier stage of heteronomy with its dependence on rules imposed from outside by adults to the stage of autonomy with its realization of one’s own moral self. Jean Piaget, among others, has discussed this transition in his The Moral Judgment of the Child (22). The initial awareness of autonomy takes the form of inversion of externally imposed rules, as many parents who have teenage children will attest.

The enormous popularity of Abramovic and her work, particularly among the elites, is paradoxical; it presents a puzzle. Since, according to the above arguments, no creation really takes place in her works, why do elites seek aesthetic gratification in them, especially since they involve physical suffering? Or rather, what do we make of the appeal of her work among the elites?

Why do spectacles of pain and suffering attract elite audiences? Unlike many poor and underprivileged, members of elite audiences are not exposed to hardships of life that we usually associate with the discomfort and suffering. Of all people, they are the ones who should be least attracted to such unseemly displays—and yet the crude fact is that they are.

We view reality through the lens of our internal mental constructs. Reality provides the nourishment to our constructs; it activates, gratifies, validates, reinforces, and conserves them. The fact that spectacles of pain and suffering attract elite audiences leads to one logical conclusion: these spectacles re-enforce their internal constructs—the lens though which they view reality. Pain and suffering are essential to this lens.

Aesthetic experience is a form of gratification. The fact that pain and suffering appeals to Abramovic’s audiences means that they derive some kind of gratification from these unseemly, if not perverse, spectacles. What they observe in her pieces feeds, sustains, and gratifies their inner constructs, thus generating aesthetic experience. To these audiences, the sights of pain and suffering serve as the affirmation of their inner self, which makes them feel gratified and “happy,” albeit in a rather perverse way.

The search for gratification is natural. All forms of life seek gratification of their functions—digestive, sexual, psychological, or others. Animals seek gratification of their animal functions, or their animal nature. Humans seek gratification of their human functions, or their human nature.

Humans are the only animals that are capable of constructing symbolic forms. Our distinct human nature—one that distinguishes us from other animals–is our capacity to create symbolic constructs that constitute the organization of our mind. The symbolic sphere has no limitations. It opens infinite possibilities for creating novelties. Since our creative activity relates to the symbolic sphere, it is not limited by any external factors or conditions. Our capacity to create is in fact infinite.

We can produce an infinite number of new levels of symbolic organization. Each new level that we create obviously has not existed before its creation. As such, it supersedes and includes the levels that precede it; and since it includes the preceding levels, it must be more powerful than they are. The creation of new and increasingly more powerful levels of mental organization gratifies our distinctly human function—the capacity to create mental constructs.

By creating new and increasingly more powerful levels of mental organization, we affirm our life as human beings, our essential humanity. When we create, we sustain our self and our civilization. The gratification of this capacity is for us the source of true human happiness.

There is only one reason why those who celebrate Abramovic’s work enjoy the sights of pain and suffering. Pain and suffering are integral to their inner life, which means that they do not gratify their creative function and, therefore, feel profoundly unhappy since they do not affirm their life in a creative act. The fact that contemporary elites totally fail to produce new ideas that could help solve our current problems is very symptomatic of their intellectual sterility. Their existential unhappiness is what attracts them to scenes of pain and suffering. The profound inner unhappiness drives them to seek confirmation of their inner experience in external objects and events.

This fact explains their perverse attraction to scenes of violence proffered by the likes of Abramovic. It may perhaps explain the decadence of contemporary elites. To paraphrase Francisco Goya, when our mind does not create, it produces monsters. The failure to create, to produce new ideas and forms can perhaps explain the pathologies that are so prevalent among the contemporary elites: their attraction to sadism, masochism, domination, pedophilia, sexual harassment and abuse.

Spectacles of pain and suffering that Abramovic stages involve the inversion of our values and norms. As has been pointed out, such inversions are characteristic for young adolescents who have not developed awareness and control of their creative powers and who affirm themselves through contradiction and inversion. Inversions do not create anything but rely on what already exists. Like parasites, inversions subsist on what is available. No matter how ingenious inversions may be, they ultimately do not gratify our creative capacity and do not make us feel happy.

For those who find spectacles of pain and suffering appealing, Abramovic’s pieces perform a therapeutic role. They externalize the inner pain and suffering that members of her audiences feel. Such externalizations open possibilities for distancing and manipulation of their inner experience and create an illusion of control.

They provide relief, however ephemeral and fleeting, from the inner pain and suffering they experience. This mechanism of externalization of inner experience as a therapeutic device works in a similar way for sadists, masochists, or psychotic killers. They also often report the feeling of calm and tranquility after they commit their horrible acts. It is indicative that when Abramovic switched to more conventional approach in her performances that avoided pain and suffering (for example, her 2019 performance “The Life” that took place in the Serpentine Gallery in London), the response of the critics and public was devastatingly negative.

One reviewer wrote, for example:

Everything Abramović is loved for is lacking. She is renowned for relating to her audience directly and uneasily, looking them in the eye. With her digital version, looking at her own hands is about as intense as it gets. Nor is there any sense of danger. Nothing is going to happen to the simulacrum Abramović, nor is anyone in the audience going to be challenged. I’ve only experienced events this vacuous at really bad concerts, when you’re miles from a band watching them on screen as they perform mechanical versions of their hits.

This defensive mechanism explains the aberrant forms of behavior so widespread among our elites. In order to feed their inner demons, some of them use displays of pain and suffering similar to those produced by Abramovic; others engage in various forms of pathological behavior. They create and observe their own demonic spectacles that involve pain and suffering, both their own and that of others.

The therapeutic effects of such spectacles do not last long. Acts of cruelty provide only a temporary relief. The catharsis that relieves inner tension passes. The experience assuages inner demons but certainly does not get rid of them. These demons demand new victims and new sacrifices in the endless ritual spectacles of violence that never completely satisfy the persistent demonic urges.

Gennady Shkliarevsky if Professor Emeritus of History at Bard College. He is the author of Labor in the Russian Revolution: Factory Committees and Trade Unions, 1917-1918 (St Martin’s Press, 1993).

Tagged with: Francisco Goya, Jean Piaget, Marina Abramovic, performance art, Serpentine Gallery, transgression