How Humor Works – A Clear Proposal For A Classic Question, Part 1 (E. Garrett Ennis)

The following is the first of a four-part series.

“Many theorists seem to confuse offering the necessary conditions for a response to count as humor with explaining why we find one thing funny rather than another. This second question, what would be sufficient for an object to be found funny, is the Holy Grail of humor studies.”

-Aaron Smuts

“No single theory yet can explain the diverse forms and functions of humor and laughter.”

-Gil Greengross & Jeffrey R. Miller

If you can read this, you’ve laughed. So has everyone else. It’s part of our human instincts, it’s part of our entertainment, it’s fundamental to human existence, and it’s actually a total mystery. According to the available sources, no one has ever come up with a satisfactory explanation for what laughter is or why people do it. But it seems like damn near everyone has tried. Plato, Aristotle, Sigmund Freud, and many, many more in recent history.

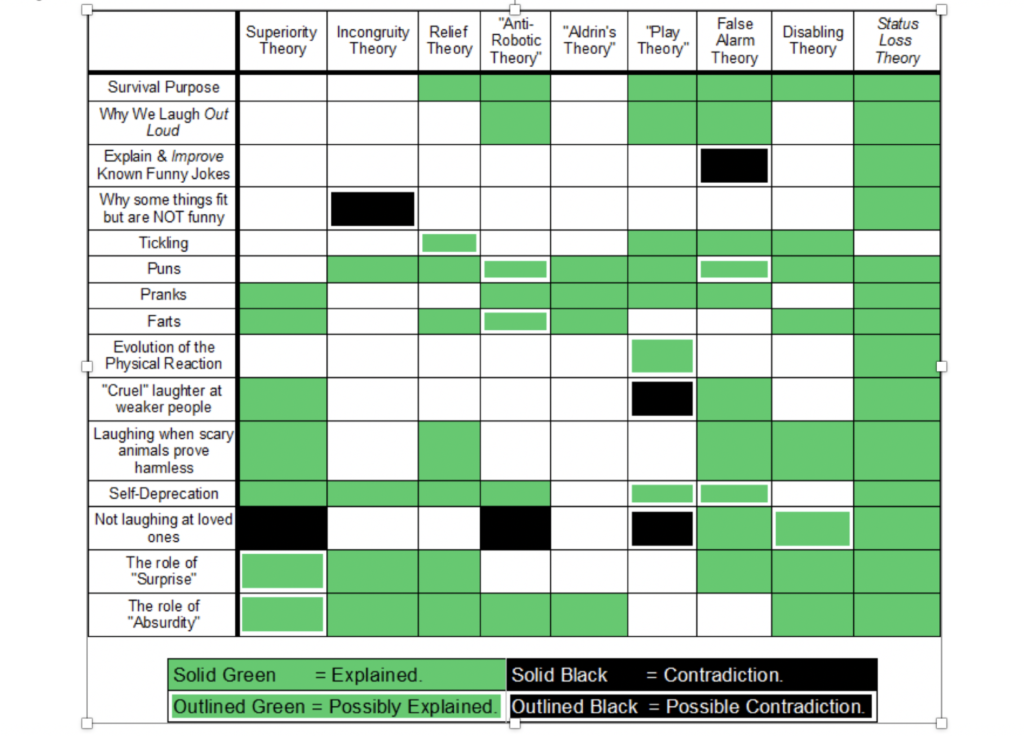

Studies have even been done of the studies, and have found or reviewed as many as a hundred possible theories, and yet and still, it’s been said multiple times that no simple, complete, and logical explanation has ever emerged. Such an explanation is so sought after in fact, that it’s reached the point of being called a “holy grail” of philosophy. With that in mind, I’m going to propose an idea that can explain the findings of the previous incomplete major theories on laughter, and if true, might even be that holy grail. But first, let’s take a quick look at some of the previous ideas, and where it seems that each works and doesn’t work:

Here are some short explanations of each theory, via wikipedia.org/wiki/Theories_of_humor, the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy at iep.utm.edu/humor, and other sources as listed:

Superiority Theory

“The passion of laughter is nothing else but sudden glory arising from some sudden conception of some eminency in ourselves, by comparison with the infirmity of others, or with our own formerly.” -Thomas Hobbes “For Aristotle, we laugh at inferior or ugly individuals, because we feel a joy at feeling superior to them.” -Wikipedia

Incongruity Theory

“The reigning theory of humor,” according to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

“In everything that is to excite a lively laugh there must be something absurd (in which the understanding, therefore, can find no satisfaction). Laughter is an affection arising from the sudden transformation of a strained expectation into nothing.” -Immanuel Kant

“A failure of a concept to account for an object of thought . . . when the particular outstrips the general, we are faced with an incongruity. The greater and more unexpected this incongruity, the more violent will be the laughter.” -Arthur Schopenhauer

“Taking pleasure in a cognitive shift.” -John Morreall

Relief Theory

“Laughter is a homeostatic mechanism by which psychological tension is reduced. Humor may thus for example serve to facilitate relief of the tension caused by one’s fears. Laughter and mirth, according to relief theory, result from this release of nervous energy.” -Wikipedia

“Anti-Robotic Theory” (Henri Bergson, 1900)

“Humor serves as a social corrective, helping people recognize behaviors that are inhospitable to human flourishing.” -Aaron Smuts, IEP

“The mechanical encrusted upon the living.” -Henri Bergson

The idea that laughter arises as a means of reminding ourselves and others not to be robotic or too automatic in our behaviors, and to accentuate the errors that arise from that mistake.

Aldrin’s Theory (Buzz Aldrin via The Ali G Show)

“Things are funny because they mix the real with the absurd.”

“Play” Theory (Max Eastman, 1936)

“Eastman considers humor to be a form of play, because humor involves a disinterested stance, certain kinds of humor involve mock aggression and insults, and because some forms of play activities result in humorous amusement.” -Aaron Smuts, IEP

False Alarm Theory (V.S. Ramachandran, 1998)

“Laughter (and humor) involves the gradual build-up of expectation (a model) followed by a sudden twist or anomaly that entails a change in the model–but only as long as the new model is non-threatening–so that there is a deflation of expectation. The loud explosive sound is produced, we suggest, to inform conspecifics that there has been a ‘false alarm’, to which they need not orient.” -Ramachandran

Disabling Theory (Wallace Chafe, 1987)

“We humans live in a world full of unique objects . . . a breeze on our cheek, the barking of a dog. That we have never experienced before. But we would be quite unable to function if everything we encountered in daily life were new and unique …” -Chafe

“Humor disables the subject’s serious relation — any relation — to the object. Wallace Chafe has called this the ‘disabling mechanism.'” –Alexander Kozintsev, 2011

The last concept on the graph is the subject of this paper. It’s called “Status Loss Theory,” and its explanation for humor and humorous laughter can be presented in pretty simple terms.

Basically, people evolved in small groups. When those groups were organized, with everyone knowing who to follow, they performed better. But if they had to fight each other for leadership, their most capable people would get hurt. Thus, over time, we as humans evolved instincts that allowed us to peacefully determine who our leaders were.

Laughter evolved for precisely this role, as a verbal signal that evolved from the gasp, which drew in oxygen at the sign of danger or harm to oneself or others, into a rapid-fire form of gasp starting from seeing specific forms of misfortune, that allowed humans (and likely some other social animals with breath control) to signal each other and peacefully determine, as a group, who they would not follow

Now, this is triggered by a specific set of circumstances in the brain, and it’s probably best expressed as an informal equation:

Humor = (Qualityexpected – Qualitydisplayed) x Noticeability x Validity Anxiety

Which can be shortened, among other ways, to H = (-ΔQ)NV / A. Either way, this states that humor is equivalent to the difference in quality between what a person expects in something and what’s actually displayed, multiplied by how noticeable the difference is, multiplied by how valid the brain finds it to be, and the whole thing divided by the amount of anxiety the person feels.

Anything that someone observes becomes sufficient to be humorous, and create laughter, as this “equation” or “ratio,” as judged by the brain, becomes greater than 0, starting in the smallest amounts with a slight diaphragm spasm, small feeling of pleasure, or partial smile. This actually, if true, is likely to be Smuts’s “Holy Grail,” so let’s go into more detail.

In order to laugh at something or someone, we must have a certain expectation in terms of that person or thing’s quality or capability that must be violated by what we actually observe. It must obviously be a noticeably wrong or low-quality thing, and the brain has to find it to be valid, and must not feel too much anxiety from what it sees or what’s going on at the time.

The “equation” form lets us show that if any one of the things multiplied in the top of the fraction are 0, then the whole equation’s result will be 0 (anything multiplied by 0 gives you 0). And if the bottom part is too large a value, it will nullify the whole thing also (by the way, if the bottom part is reduced to 0, it will of course render the equation undefined, if this is bothersome, it can just as easily be imagined as “Anxiety + 1”).

So if we don’t laugh at something, it’s because…

- We didn’t expect a high enough quality of it. For example, humble people get mocked or laughed at far less than those who are arrogant or try to create high expectations of themselves. Also, as we laugh at something, our expectations lower, so it must go lower in quality in new ways to stay funny. Which is why a repeated joke gets less and less funny.

- We don’t find what’s been displayed to be low quality. For example, many people won’t laugh at “gay teasing” (like “how about a skirt to go with that martini?”) because they don’t feel that being gay is a low-quality trait.

- The error isn’t noticeable to us. For example, people in physics may have “inside” jokes that require some knowledge of the field to identify, which I personally won’t notice.

- Our brain doesn’t find the error to be valid. Jokes that are “corny” or “cheesy” are not believable or valid to the brain. But also, the brain judges misplacements of things as errors, and if the misplacement isn’t a close-enough mistake (i.e. something that does have something in common with where it’s incorrectly put), then the brain doesn’t find it valid and won’t laugh. Note that the error itself must be valid, not the method of showing it. So a puppet can make us laugh, if the puppet is showing a valid weakness or error in someone or something else.

- We feel too much anxiety. Since, according to our theory, laughter is supposed to be a way of peacefully forming a social order, we won’t laugh if we feel there is a threat of violence from the person who is going to lose status from it, or if we may be in a situation where making noise is dangerous, OR if we worry a loved one will lose status because of our laughter. Thus, the general feeling of anxiety nullifies laughter. This includes anxiety from other sources too, thus, if a loved one just died, you’re unlikely to laugh at anything. Which means that when we say a joke is “too soon,” it means we still have anxiety associated with the subject.

Humor and laughter result when all of these are satisfied. Also, if we notice multiple quality gaps at once, the humor is increased, but we’ll discuss that more in our examples.

Right now, let’s take the time to point out one of the strongest arguments for this concept, which is that it explains and predicts essentially everything about humor, including the findings of the previous theories. Some noticed that there must be a “surprise” or an “expectation” to be violated. This is explained clearly and logically here, by the idea that laughter functions to lower people to a new status as they demonstrate ability below what others thought.

“Absurdity” makes something funny because it’s a highly-noticeable error. The need for validity, as said, shows why “cheesy” and “corny” jokes aren’t funny. Furthermore, since this is meant to function without violence, it follows naturally that we’d smile when we laughed, to indicate no threat to each other, and feel pleasure while we do so, to further suppress any anger.

Furthermore, since a laugh is a signal to others, we laugh as an instant reflex, allowing others to see what’s happened and thus also observe whatever’s changing the status quo in our group, especially pre-language. We often can’t explain why we laugh because, due to the benefits of laughing instantaneously, it triggers off of instinctive recognition at the precise moment, where we don’t always have the words to explain it. This also easily shows how laughter can exist in various forms in certain other social animals who don’t have language.

Let’s note also that this theory can clearly explain the idea of “sense of humor.” Which consists of what someone personally finds to be high-quality and low-quality (see the previous example about certain gay jokes, or things like English humor which depend on high expectations of people with certain accents and postures, which aren’t shared outside the country), the types of errors they can notice (such as their knowledge base for “inside jokes,” as well as someone’s wittiness consisting of their ability to detect subtle errors or signs of low-quality), what they personally find believable (children, for example, enjoy cartoons and other types of humor which adults don’t find nearly as funny), and what causes someone personally to feel anxiety (it’s been said before that rich or powerful people tend to have loud, boisterous laughs, which this theory predicts since they feel less anxiety or threat than the average person).

Okay. If this is true, why hasn’t it been found before?

Good question. Perhaps, like a lot of ideas, this builds upon certain others, that must be known first, and which the internet has made publicly accessible. Particularly evolution, which means that Aristotle, Plato, and basically anyone who lived before 1859 had major gaps in their path toward finding this. In addition, this relies heavily on the idea that people developed in small social communities, a concept I call “the Village Brain,” which also can solve at least one other mystery of human instinct. Here it may not be essential, but understanding it certainly helps.

Furthermore, there’s a tension in the brain’s measurement between noticeability and validity. An error or sign of unexpectedly low-quality has to be close enough to reality (or a misplacement close enough to being correct) for the brain to judge that someone has genuinely made a mistake, but it must also be wrong enough to be noticeable. This is why a lot of absurd things or jokes are too corny/invalid to be funny, and a lot of more subtle jokes must expose a noticeable enough mistake for people to “get it.” The challenge of striking this balance is a huge part of why it’s difficult to write a good joke.

On top of that, this fairly simple mechanism of humor actually expresses itself in many distinct ways (like how the simple mechanisms of variation and selection express themselves in many ways in evolution), which can make it hard to recognize the common source. For example, there are actually at least four distinct types of humorous laugh. Laughter at a known third person’s low-quality, which is the most common, but also first-person, at one’s own errors (like when you realize you’ve been looking for your hat while you’re already wearing it), as well as second-person laughter, such as laughing at someone’s failed attempt to tell you a joke.

Lastly, there’s laughter at an unknown third person, when you discover an error by someone unseen, which gets compared to your expectation of the average person around you, such as might occur when you come across a car parked with one wheel up on the curb.

Now, we will go through a thorough list of different types of humor, including modern and older examples of humor, describing what makes them work and how the theory applies to them, and also demonstrate some other useful applications that come from the idea, including explaining far more, possibly all, of our common sayings about the topic.

The point here is to go beyond claiming that the theory is the most expansive basis for humor studies, by showing it, as well as hopefully to provide a feel for how the idea works to help understand humor in general and even function to create and improve jokes.

All of this is or was far beyond the scope of basically the entire volume of humor theory that currently exists, and can be done here in clear and simple terms, using only our core concept and informal equation, without the need for large amounts of additional jargon or even complex language.

As a brief review, the Status Loss Theory states that humor and humorous laughter developed as a way for people to peacefully move each other down in status in their ancient village groups, since these villages benefited from having clear leaders, but fighting for leadership would only harm the most fit people there. The pleasure we feel is to reduce any chance of aggression at these moments, and the smile helps to show the same indication of peace to our peers. Its function, the way the brain determines when something is humorous, can be modeled as: Humor = ((Qualityexpected – Qualitydisplayed) * Noticeability * Validity) / Anxiety.

While these variables probably can’t be measured, their ratio and relationships are reflected extremely well in this informal equation format. We covered the basics of it here previously, but they should become clear again, and hopefully more clear, as we go through things.

E. Garrett Ennis is a writer, vlogger, and columnist with an academic background in philosophy who has published widely on the subject of irrationality and has a popular YouTube channel known as StoryBrain.

Tagged with: absurdity, false alarm theory, humor, laughter, relief theory