Professional Dress Codes Lack “Authenticity” For Millennial Generation (Rebekah Gordon)

I worked at a bank for a year and a half between the completion of my undergraduate degree and the beginning of my master’s. Our dress code, which by many standards was relatively lenient, included multiple strictures.

For example:

Whether or not you regularly meet the public, you are required to comply with these guidelines:

Visible personal decorations such as tattoos or body piercings (other than non-distracting earrings) should be covered or removed during working hours;

Multi-colored or other hairstyles that are distracting to customers are not permissible in the workplace;

All attire should be clean and neatly pressed. Women should keep the length of their skirts/dresses at an appropriate length for the office;

You are expected to use good grooming and hygiene practices…

The list also gave examples of unacceptable attire, which it claimed were merely “illustrative” and “not all-inclusive.” For instance:

Tank tops, camisoles and spaghetti strap tops or dresses (These items may be permissible if worn with a jacket);

T-shirts, midriff baring or strapless tops;

Leggings, tight fitting stretch pants or other close form fitting apparel

Sweatshirts or sweatpants;

Shorts of any style (Bermuda, city shorts, short shorts, or skorts);

Denim of any color, which includes denim jackets, denim skirts and blue jeans (may be permitted on officially designated dress down days, such as UCP Casual Day);

Clothing with printed character/advertisement which covers the front and/or back (Chest pocket logos are acceptable);

Any clothing bearing references to sex or sexual activity, obscene or inappropriate language or the promotion or use of illegal drugs

Hats or caps…

During this time, I desperately wanted to dye my hair purple, but I waited until after I left my job to do so, because I was well aware that purple hair would be considered “unprofessional”. I began my job with the knowledge that such choices would not be permitted – and so I was not upset or bitter about the restrictions of my appearance- but many millennials are.

This restriction of creative expression greatly offends many of my generation who value self-expression and authenticity above most things. They want the ability to “be themselves” – hair dye, piercings, tattoos, etc.- at their place of employment. After all, we ask, isn’t “professional” an arbitrary category?

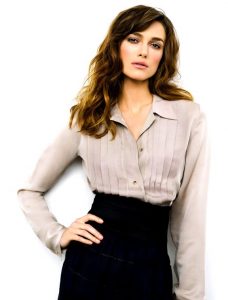

What makes this…

….any more professional than this?

Who decides what is and isn’t appropriate in the workplace – and to what end?

In 1977 Richard Brimley, a Connecticut English teacher, refused to wear a tie to his classes in direct defiance of his school’s policy, asserting that not wearing a tie was his constitutionally protected right as symbolic speech. He claimed not wearing a tie helped his students relate with him better. In the ensuing legal battle of East Hartford Education Association v. Board of Education, the court ruled that it was “in the school board’s interest to promote respect for authority and traditional values, as well as classroom discipline, by requiring teachers to dress in a professional manner”. The guidelines for professionality are not laid out in the verdict of the case, leaving that decision up to the school board to determine.

In his book Discipline and Punish twentieth century French philosopher Michel Foucault posited a concept he called “docile bodies”, one that views the body as a malleable object on which disciplinary force is acted. For Foucault, the body is one small part in the complex arena in which power is organized and arranged.

We see this in Brimley’s case. The disciplinary force of his employer as well as the Second Circuit Court of Appeals acted upon him in forcing his conformity to a “professional” manner of dress. Power structures have been affecting the ways in which individuals dress for thousands of years in a myriad of ways for a plethora of reasons.

Large military forces as ancient as the Romans Empire used uniforms to distinguish themselves from those around them. As Foucault points out, prisons use uniforms to strip the individual of their identity. Fast food restaurants, to private schools, to musical groups all employ the use of uniform. Uniforms by definition create “uniformity”. They highlight sameness – to the exclusion of others. This accomplishes control. It either venerates or denigrates of those in uniform by distinguishing them as separate from everyone else.

As Ruth Rubenstein notes in her book Dress Codes: Meanings and Messages in American Culture, “standardized modes of dress offered a protective ‘cover up’ at a time…when the distinction between private space and public space first emerged. When one lived and worked amongst strangers rather than among family members, there was a need to protect one’s self and one’s inner feelings. Wearing the expected mode of dress enabled individuals to move easily between the various spheres of social life… Clothing provides a buffer between the public and private self. ”

At the time of their imposition standardized modes of professional dress were largely appreciated by those on whom they were enacted (though not by all as we saw in the Brimley case). But as generations change, so do their values, and a buffer between the public and private self is not even remotely desired by millennials. Authenticity and self-expression rank considerably higher than concerns of privacy with those who are now entering the workforce.

Workplace dress codes, like their more stringent uniform counterparts, are also an intentional way of “othering”. They set employees apart from those they are serving. But often, dress codes accomplish other unintended, subconscious discriminations by class, race, and gender. If you cannot afford nice clothes to wear for a job interview, you’re probably not getting that job, regardless of your skill.

Black women are still being told that the hair that naturally grows out of their heads is not professional and must be subjected to chemical treatments or covered before it is acceptable. Women in general are disproportionately taken to task for dress code violations (indicating the heavily policing of the female body).

Most “professional” dress codes are not transgender inclusive. Dress codes, and the concept of “professionalism” determine who is “in” and who is “out” – skewed in favor of cisgendered, white, upper class males – to the detriment of both people seeking employment and the institutions looking to hire. While the setting apart of employees from others is not inherently an evil, the way in which that that has been accomplished is unjust.

I will always think a man in a suit is more professional, or respectable, than a man in cheeto-stained sweats. There is some standard for appropriate dress, whatever that may be. I have been indoctrinated by the gospel of professionalism. But I can and must acknowledge that many of the things which I and society at large perceive as appropriately professional are sincerely biased and in need of reform.

Rebekah Gordon is a graduate in the Religious Studies department at the University of Denver. She is a poet and a musician in addition to an academic, and is an editor for Esthesis. Her interests range from secular-sacred relations in America to religious fiction, semiotics, and redemption theology.

Tagged with: creative expression, Michel Foucault, millennial generation, professional dress, Richard Brimley, uniforms