Making Mesoamerica Visible In The Discourse Of Contemporary Art And Ecology (Elliott Jenkins)

“In our everyday lived experience, there is an unforgiving momentum to adopt ways of being that are Eurocentric within a coloniality of power, especially in schools.” -Cueponcaxochitl Dianna Moreno Sandoval

In order to recognize human impact on the environment, it is first important to understand our relationship with our planet – and all living organisms. Thus, the scientific analysis known as ecology is crucial for gaining such understanding.

Since ecology is defined by Jonathan Benthall as “the study of organisms in their surroundings or habitats,” it is essential in this field to recognize how different beings affect each other and their surroundings. While it is encouraging that artists deal with these issues and that there are art historical discussions on the protection of the environment, the conversation seems to only begin with art and artists from the mid-twentieth century.

When pre-twentieth century art is discussed in the ecological conversation, it is typically work created by an artist from a dominant culture in Europe or the United States. This exclusivity informs the central argument of this paper: the concept of ecology is important in shaping research in contemporary art, but in order to fully harness its potential, its deficiencies must be looked at critically. This criticality means that it must be fully realized that humanity’s place in the natural world has been the subject of artistic mediums for centuries, not just in the contemporary age.

One area of the world in which this relationship was immensely present was the art of pre- Columbia Mesoamerica. By looking at writings on contemporary art, ecology, and Mesoamerican art, as well as an example of a contemporary artwork, it will be proven that pre- Columbian art is invisible within historical narratives and contextualization; which in turn, can have the potential to shape how we research and write about art and ecology.

The discourse surrounding the relationship between contemporary art and ecology began taking shape in the mid-20th century with scholars such as Benthall. In his 1969 essay, “The Relevance of Ecology,” Benthall explains that ecology is relevant for artistic practices because “ecology offers a way of translating artist’s traditional reverence for life into an exact and up-to-date knowledge of the origins and functioning of life.” Benthall implies that having an ecological base for art can reflect the current times and what we value as a society. I contend that this is true in the actual practice of art but it is also true in the writing and analyzation of such practices. In other words, the way we write about art and ecology reflects the values of society based on what we write about and what we choose to omit.

The way in which omission decisively reflects not only Benthall’s values, but values that have been engrained in Western society, is evident in his discussion of religion and its importance to art and ecology. He argues that there has always been a direct link between nature and religion when he explains that Christian iconography is ecological. He states that, “[o]ne has only to think of the Christian symbolism of the lamb, the fish, bread and wine, the Nativity in a stable; or of the poetic strength of the Anglican burial service. Religion might be described as a transfigured ecology.”

This interpretation of ancient Christian artistic motifs as ecological is important because it demonstrates that these subjects have been present in art for centuries. However, only Christianity is discussed as a source for religion’s relationship with nature. No other non- dominant culture or religion is explored, most of which would arguably have made his case more convincing.

A similar case in which writing about ecology and art reveals an inability to situate certain cultures within dominant discourses is Andrew Brown’s book Art & Ecology Now. The book surveys the rise of ecologically conscious art and begins with an introduction which acknowledges that “[a]rtists have always been inspired by the beauty and mystery of nature, of course, and have used elements of the natural world in creative ways for centuries.”(6)

Brown reviews the “historical basis” for contemporary ecological art starting with the archetypal beginning of art history – the paintings in the Lascaux cave complex. Brown then uses the early Renaissance painting and Dutch Golden Age painting as examples of early depictions of humanity’s relationship with the natural and built environments. He continues on to cite Romantic period artists in Europe such as William Blake or Casper David Friedrich and American artists like Thomas Cole, whose artwork was starting to become ecologically conscious and attempted to grapple with humanity’s impact on the climate.

While it is recognized that the aim of this book is to discuss the current state of ecology in contemporary art, it is still perturbing that there is no mention of artistic traditions outside of Europe and the United States, especially in cultures and religions that have had the intersection of mankind and Mother Earth at the center of their beliefs – cultures such as those found within the “New World.” The fact that art from pre-Columbian Mesoamerica – along with a myriad of other cultures – is overlooked when discussing the historical impacts on contemporary ecological art forms can be attributed to the fact that contemporary art has an increasingly secular identity even within the research and writing surrounding it.

Despite this secularity, it is still imperative to consider and discuss religious or spiritually-centered cultures, especially marginalized ones, within the context of contemporary artistic trends.The ability of hegemonic powers to shape the trajectory of art history in order to reflect current societal values is evident in Benthall and Brown, and this systemic issue may be illuminated best by pre-Columbian art historian Esther Pasztory.

In her 1990 essay “Still Invisible: The Problem of the Aesthetics of Abstraction for Pre-Columbian Art and Its Implications for Other Cultures,” Pasztory offers an explanation as to why the art produced by these cultures are received with emotions of curiosity and novelty which therefore void them of legitimacy. Pasztory opens the essay with an anecdote of Albrecht Dürer visiting the Town Hall of Brussels in 1520, in which Mexican artifacts were on display. He discusses these objects in his travel diary but does not seem to find enthusiastic words about them and does not sketch any of the objects.

However, he finds time to sketch and write positive prose about a fish bone, a large bed, and Roman columns. Pasztory attributes Dürer’s lack of interaction with these objects to the Western “inability to comprehend an alien culture” until the late 19th or early 20th century. She explains that any “attempts to describe or to depict them were generally in terms of their similarity or dissimilarity to Negro or Caucasian types […].” (106) Therefore, classical ideals were still the standard for art and anything else was written off as primitive artifacts or curiosities – objects to be admired but never praised for artistic virtuosity.

While these dominant classical aesthetic constructs were challenged by the rise of Modernism, Pasztory explains that Modernism still ultimately exploited these cultures and dictated their overall value. Pre-Columbian art only gained importance and validation from modern artists such as Henry Moore and Pablo Picasso because the “primitive” nature of it had value to them and their creative aspirations– not because they saw the art to have autonomous merit.

Pasztory discusses the highly controversial 1984 exhibition, “’Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern“, at The Museum of Modern Art as a moment that illuminates the domination and control of Western traditions over art from cultures that are deemed “primitive.” She argues that the exhibition perpetuates the notion that was thought even during Dürer’s visit to Brussels: “Tribal artists use abstract forms because that is their inherited tradition and, rather than innovating and experimenting with visual forms, they stick to tradition. Their abstraction is a lack of imagination, while ours is the height of imagination.”(110)

While it is imagined that the goal of contemporary art has drastically changed for the better since this exhibition, it is hard to defend this sentiment when critically examining the current state of research and writing on ecology and contemporary art practices. It is not difficult to find examples of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican artworks that make the case that art produced within these cultures must be considered in the research of the history of ecological art.

In terms of a tangible work, Pasztory uses a mural from the Tepantitla apartment compound at Teotihuacan (Fig. 1) to further her own argument. It is also a pertinent example for this present argument.

The mural depicts a goddess with a massive tree sprouting from behind her head, upon which there are flowers and various birds. Water flows out of her open palms and Pasztory notes that the storm deity Tlaloc is shown surrounding her in the painting’s border. From this depiction alone, it clear that the very culture and spiritual nature of the Mesoamerican people is completely entwined with the natural world. Their very existence is non-divisible and dependent on animals and elements, as well as the gods and goddesses that represent these natural wonders.

Apart from looking at formal aspects of Mesoamerican art, it is important to look at specific beliefs that are the backbone of the art. One such belief, the notion known as “co-essences,” sheds light on the relevance of Mesoamerican culture in the study of ecology. Co-essences, or as Stephen Houston and David Stuart say, “companion spirit,” illustrates quite clearly the relationship the Mesoamerican people had with the natural world and beyond.

In “The Way Glyph: Evidence for ‘Co-essences’ among the Classic Maya,” the authors discuss that not only do “Maya hieroglyphs and art indeed document the notion of a companion spirit” but that this belief is “central to much of Classic Maya art and religion.”(1) The term “co-essence,” which is attributed to historian John Monaghan, is defined as “an animal or celestial phenomenon (e.g., rain, lightning, wind) that is believed to share in the consciousness of the person who ‘owns’ it.”(1-2)

Houston and Stuart explain that this “linkage is so close that when the co-essence is wounded or destroyed, the owner grows ill or dies.” The co-essence is “embedded in the heart” and “individuals and gods may have more than one co-essence, particularly if the owner is powerful or spiritually knowledgeable.”(2) These co-essences can take many forms, such as reptiles, birds, flying jaguars, huge bucks, or “peculiar composite creatures.”

It is important to note that the prominence of these composite co-essences that are intertwined with a multitude of beings relates directly to Esther Pasztory’s argument that European scholars barely attempted to write about or research such Mesoamerican artifacts because of their abstract and supernatural nature.

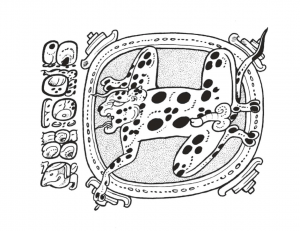

This composite creature is most common and is used as an example by the authors when discussing a way glyph of a Seibal lord (Fig. 2). The glyph depicts a “water-jaguar” and the authors use this glyph found on an altar vase as an

example of the relationship with “creatures and historical figures to whom they pertain.”(6) This visual characteristic is a powerful one because it shows not only a relationship between a singular Mayan lord and a singular animal, but an amalgamation of various creatures – a view that is related to ecology in terms of how all living beings affect the changes Earth undergoes.

An equally important point to note in Houston and Stuart’s study of co-essences, is that one of their main goals is to debunk the idea that the glyphs, commonly found on pottery vessels, are related to “death and the afterlife” and that the figures represent “gods, underworld denizens, or deities.”(7) The authors argue that the glyphs instead represent co-essences and extensions of the human being. This idea that the vessels exhibit underworld beings related to witchcraft, as well as images seen as heretical and deviant practices, was specifically perpetuated by European colonizers. The authors state that “[w]ithin a few centuries of the conquest spirit companions had joined the witches, demons, and lycanthropes of the Spanish Colonial imagination.”(2)

According to the authors’ study of the meaning of way and the imagery on the pottery, the Europeans completely redirected and imposed their own meaning onto these central beliefs of the Mayan people. This is directly correlated to Pasztory’s argument that Mesoamerican art was invisible to those who studied the history of art in pre-Modern Europe and that it’s significance was controlled by those who led the Modernism movement.

By examining this research from Houston and Stuart and Pasztory, it is surprising that neither Benthall nor Brown contributed any cultures, such as those within Mesoamerica, to their argument in regards to the history of art and ecology; especially since the art from these regions exhibited a deep regard for the relationships between living and non-living organisms – arguably the most important aspect of life on Earth.

Throughout this argument, the case has been made that Mesoamerican art – amongst other cultures – has been neglected within the discourse of the history of ecology and art. To further understand the need to include Mesoamerican art, it will be helpful to look at an artist who creates extensively researched-based artworks that are related to communication, corrupted translations, and the connection and impact that humans have with their ecosystems. Sarah Rose, a Glasgow based artist, presented a solo show in 2016 entitled Difficult Mothers at SWG3 Gallery.

The exhibition (Fig. 3) took up these issues of our relationship with and effect on climate and the environment. The name itself came from writer and critic Arne De Boever who used the phrase when discussing “concepts of mothering following our uncertain and dangerous relationship to climate.” The show consisted of various objects such as glass balls scattered on the concrete floor, ecological print works pinned to the white wall, and speakers projecting distracting sounds and conversations.

The chaotic placement of these objects within the space resonates directly with the study of ecology because of the way in which it makes us aware of our relationship to the environment. Therefore, Rose fits into the narrative proposed by Benthall and Brown, but her work also sheds light on the way that dominant forces subjugate environments that are seemingly incomprehensible because of their abstract or organic nature.

This idea is most evident within her sound installations, which Rosie Aspinall Priest points out in her review of the show as the disembodied sound pieces which call attention to “the organic aspects of our surroundings and those which are man made.” The voices exert power over the the wall prints and glass orbs. Cacophonous sound dominates and distracts viewers from these organic objects. Priest, in her review, equates Rose’s exhibition to the writings of Lisa Blackman. In her essay, “The Dissociation of Anxiety,” Blackman discusses voices of authority and the reasons this gives viewers anxiety – a feeling that is ultimately related to control.

Blackman goes on to say, “[t]he exercise of control historically became tied to the capacity to be able to enact clear and distinct boundaries between the self and other.”(6) Blackman’s ideas related to Rose’s sound pieces because they are a means to divide the organic from the manufactured – the dominant forces control the general perception. The human voice has often been used throughout history to divide humanity from their natural surroundings. In this sense, Rose’s voices relate not only to how humanity treats their environments but also to the way Eurocentric discourse of art and ecology renders cultures, invisible because they do not fit within dominant paradigms – cultures which are immensely important for how we look at our relationship with the natural world.

Within the research and writings on the importance of ecology in contemporary art and the history that has lead to this point, the problem lies not within discussing Renaissance painting or Dutch still-lifes. It is the negligence of avoiding cultures that were based on the belief that there is essentially no separation between the human body and all other organisms.

As the relationship between ecology and art is still at the early days of discussion, I believe this critical exploration into why pre-Columbian art and culture is left out of the historical scope is important moving forward. Certainly there are countless cultures with artistic production that would illustrate this point as well, but Mesoamerica specifically has a history engrained in domination by Western powers. It seems to be in a similar state in contemporary society, as Benthall and Brown both illustrated through their desire to advocate for a new age of environmentally conscious art as if there never have been cultures that emphasized relationships in the natural world.

When discussing theorists’ obsession for ground-breaking art, Blackman says that “[t]his call for a paradigm shift across the humanities is undermining the capacity for ideological critique important for challenging inequities and oppressions.”(ix) In other words, if we write about contemporary art history as if it is creating brand new ways of looking at the world, then the dominant culture that is writing and being educated about these perceived changes controls what is celebrated and what is invisible.

In order to comprehensively recognize what came before this significant concept present in contemporary art discourse, we must inclusively and critically look at how we reached this moment in history; and indeed, advocate for those cultures and peoples whose art has been marginalized from the principle art historical narratives.

Elliott Jenkins is Adjunct Professor in Art History at the Cleveland Institute of Art. He holds an MSc in Modern and Contemporary Art from the University of Edinburgh.

Tagged with: Andrew Brown, contemporary art, ecology, Esther Pasztory, Jonathan Benthall, Mesomamerica, modernism, primitivism, Thomas Cole