How To Talk About Art, Part 3 – Interrogating What We See (Rebekah Gordon)

The following is the third of a three-part series. The first installment can be found here, the second here.

In the past two installments of our “How to Talk About Art” series, we discussed the nature of art and the predominant forms which it takes. This installment tackles the many and varied ways in which we question art. The questions which aid in art analysis fall into one of two predominant categories – formal or contextual.

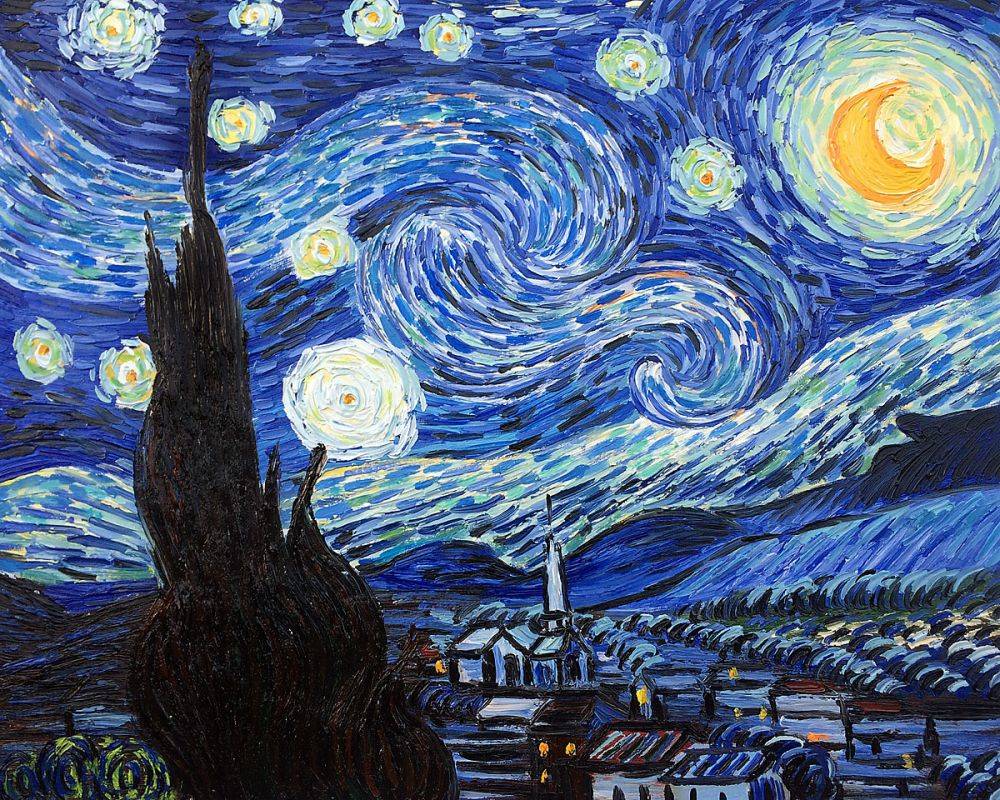

In formal analysis the questions used pertain directly to what is seen in the art piece itself. These questions involve composition, materials, technique, and subject matter. This kind of analysis is better seen than described, so below the four primary modes of formal analysis listed above will be applied to Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night.

Composition

Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night features a large cypress tree in the foreground, a small town in the middle ground, and a swirling night sky in the background. The cypress tree sits in the bottom left of the foreground, and the moon shines from the upper righthand corner of the background – bringing balance to the painting, leaving the town and mountains below seemingly suspended in between.

Materials

Starry Night is a 29″ x 3 1/4″ oil on canvas, painted predominantly with the cooler end of the colour spectrum.

Technique

This post-Impressionist work of art uses lines in lieu of solid silhouettes to portray this night scene, swirling and fluid as opposed to solid. Thick brush strokes, for which Van Gogh was famous, are over-emphasized and add depth and texture to the canvas. The colors he selected for Starry Night draw attention to the sky, contrasting its brightness with the darkness of the town below.

Subject matter

Starry Night is a representation of the view from Van Gogh’s studio window at the St. Paul de Mausole Asylum conflated with the town of Saint-Rémy de Provence. Both the cypress tree in the foreground and the church steeple in the middle ground point towards the focus of the painting – the sky.

Formal analysis breaks works of art down to their most basic components and uses them as standards by which to judge art quality. Quality, however, is not the only concern of those who critique art. Quality stands hand in hand with impact. Impact is ascertained via an entirely different line of questioning: contextual analysis.

Contextual Analysis consists of questions regarding intention, reception, and process. It questions not what is in the work of art but what is beyond it.

Questions of intention ask what the artist intends his/her audience to understand. Is the message of the piece religious? Is it political? Was it meant to make us ask questions or tell us something specific?

Questions of reception ask what community or audience the art was created for and where that work is it being presented. Like the Fearless Girl of Wall Street, does the work of art play off of its surroundings in any specific way? Does it incorporate its environment? Is it meant only for people of a certain heritage or faith? Questions of intention and reception star in debates about cultural appropriation in art.

Questions of process ask what stages the artist had to go through when creating the work. Is the work of art carved or painted? Was the paint made from something specific by the artist? Is it made of found objects that the artist had to collect, then assemble? Was anything melted or changed/distorted in form? Art is as varied as people themselves, and as such, is created through a seemingly infinite number of methods.

Both formal and contextual analysis enable the viewer to better understand the art which they are viewing. Formal analysis enlightens individuals about the technical elements which comprise the work of art, and contextual analysis gives the reasons and methods behind the creation of the work. While both offer unique things and speak to different questions and spheres of influence on an individual basis, art is best understood when both modes of questioning are employed.

Rebekah Gordon is a graduate student n the Religious Studies department at the University of Denver. She is a poet and a musician in addition to an academic, and is an assistant editor for Esthesis. Her interests range from secular-sacred relations in America to religious fiction and semiotics.

Tagged with: composition, how to talk about art, Saint-Rémy de Provence, Starry Night, Van Gogh