Death Of Christ/Death Of the Artist – The Slippage Of Meaning In Contemporary Performance Art And Photography (Urszula Szulakowska)

Note: The works of Krzysztof Gliszczyński depicted in the text of the article below are reproduced through permission obtained by the author.

From the late 19th century and early 20th century in western Europe, the modernist avant-garde was developing a new concept of its political, social and cultural role. In the framing of the self-image of the artist and his public persona, the concept of Christ the Messiah was fundamental.

An image of the male artist (and writer and poet) was promoted in which he became a messianic figure whose political purpose was to lead society from corrupted bourgeois culture to an enlightened Utopian society by rejecting traditional academic creative modes in favour of new subject matter expressed in experimental forms and materials.

The products of this experimentation became, in effect, religious icons, gateways to higher levels of consciousness, as in the works of Malevich, Mondrian, Delaunay, the Futurist group and many Surrealists.

This strange situation in which art became a religious cult with strong Christological overtones, as I have written in Alchemy in Contemporary Art, was the result of the existential vacuum in the social psyche of western Europe caused by the retreat of institutionalized religious belief (1-5). This absence of the divine order in social and cultural spheres after the Enlightenment was partly alleviated through the fetishism of art products and by the new image of the artist as priest-like, both a mystical seer and political revolutionary.

However, this trace in modernist art of Christian dogma was also involved with pagan spiritual meanings as in the figure of the Hermetic magus and the Theosophical medium.

The magus is an ambiguous figure created in the 16th century magical writings of pagan influenced natural philosophers – Cornelius Agrippa most especially. According to G. E. Szőnyi’s John Dee’s Occultism: Magical Exhaltation through Powerful Signs, Cornelius Agrippa’s ideas were based on Hellenistic hermetic texts of the 2nd century, themselves influenced by early Christianity (169-74, 236-40).

The magus was both divine and human, glorified and suffering, and his esoteric knowledge was placed at the service of humanity. In the mid-19th century, the imagery of the Messiah Christ and the magus underlay the teachings of the Eliphas Levi in the occultist revival in Paris which was closely related to modernist artistic developments. Levi’s concept of the magus had a significant influence on the artistic and political practice of Andre Breton and the Surrealists.

The Polish historian of magic and alchemy, Rafał Prinke, has examined the effect of the ideas of the Polish magus and cultural theorist Józef Maria Hoene-Wronski on the French avant-garde. Wronski was a political messianist who anticipated social and political redemption for his country Poland in recompense for her Christ-like sufferings during the partitions from 1772. Wronski influenced the Polish poet in exile, Adam Mickiewicz, who was also a theosophist and a disciple of Jacob Boehme.

It was Mickiewicz who was the source for Eliphas Levi’s messianism in which the modern magus would be a Christ-like figure who would suffer and be sacrificed for a political and spiritual cause. This, in turn, was adopted by the French Symbolists and Surrealists as an image for the avant-garde artist, as we find in R. T. Prinke’s “Uczeń Wrońskiego –Éliphas Lévi w Kręgu Polskich Mesjanistów” (133-54).

In the 1970s, as a result of the criticism of left wing radical cultural historians and feminists, the messianic role of the male artist came under scrutiny and his cynical complicity in the investment market of international capitalism was exposed, as noted in Bernard Smith’s The Death of the Artist as Hero: Essays in History and Culture. Further, the ideas of French and German post-structuralists, such as Roland Barthes’s essay “The Death of the Author” in 1967 and the neo-Marxist Frankfurt School (including theorists such as Habermas) were widely influential on American and British critics, theorists and historian (383-86).

Such radical leftist critiques rejected the vision of the male artist as a self-directed creator of his work, in favour of a notion that it was not the author/artist who created the meaning and purpose of the art-work, but rather the recipient audience. According to this theoretical model, the artist was no more than a transmitter of pre-existing texts. This denial of the possibility of artistic originality was instrumental in killing painting (and free-standing sculpture) as a valid art form and a commercial commodity throughout the 1970s in favour of conceptual and performative modes, as stated in Lucy Lippard in Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art object from 1966 to 1972.

It was the cloak of religiosity and magic, that was ripped away from the male artist. This process lasted through into the early 1980s when the pressure of market forces retrieved painting as a market commodity in a pseudo-movement loosely described as neo-expressionism, but only male artists were involved. Neo-expressionist artists returned to the portrayal of the human body and to mythical subjects, which can be seen in the exhibition of A New Spirit in Painting.

The art-works often carried abject Christological references in which the degraded body of Christ became a self-portrait of the artist himself. However, Hal Foster in Recodings notes that a sense of hopelessness pervaded, and the messianic role of the artist was lost, leaving only the investment cult of the artist’s signature.

In Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, Christ’s body had been perfect and sexually potent – for example, Leo Steinberg’s The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, a well-known analysis of depictions of Christ in the 15th and 16th centuries. However, in northern European art in this period there was another, quite different, vision of the body of Christ on the cross which was that of Everyman dying neglected and alone.

This was a castrated body. Nevertheless, for example, in the Isenheim altar painted by the Germans Niclaus of Haguenau and Matthias Grünewald in 1512–1516, the wounded body of Christ-Everyman is resurrected in a perfected glorious body in the central panel.

In contrast, when the Christ image was used by male expressionist artists in the 1980s, it was only as a castrated body, a reflection of their own sense of futility. Specific examples of this are the noteworthy series of performance photographs by the German artist Arnulf Rainer in which he is shown crucified on a cross, as in the Isenheim crucifixion.

Another German artist fixated on the sign of the cross and on grotesque appropriations of the crucified Christ is Jiri Dokoupil who has used this theme of crucifixion for several decades since the 1980s. Occasionally, Dokoupil included representations of Christ hanging on the cross appropriated from artists such as Rembrandt, as can be seen in A. Bonito Oliva’s Trans-Avantgarde International.

A less frequent image in recent art is that of the Dead Christ in the tomb. The prototypes usually are the Christ in the Tomb with Two Mourners by Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1490) and more rarely, Hans Holbein’s Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, 1520-22, where the figure of Christ is shown totally alone in the tomb, decaying.

This type of Renaissance religious imagery has had a great influence on the Italian film director, poet and writer Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-65) who, despite his left-wing ideology, in the design of his filmic mis-en-scene often took recourse to the religious tradition of western painting. This can be seen in Silvia Minguzzi’s Pasolini on Mantega- Lamentation over the Dead Christ and Sam Rohdie’s The Passion of Pier Paolo Pasolini (122-24). Pasolini was interested in the conflicting ideological scenarios that are encapsulated in famous masterpieces.

In the famous last scene from Mama Roma (1962), Pasolini recreates Mantegna’s Lamentation when Ettore, the hero, dies in a prison hospital. Here, he expresses his feelings of empathy with the underdog, the dispossessed of society, the marginalized. The camera shoots his body from Ettore’s feet. Pasolini often uses the word “sacred” to describe his images by means of which he infers the other images that are present in the mis-en-scene but are excluded from the frame. Pasolini creates the sense that what is visible in his film is just one aspect of reality and that the essential — and sacred — aspect, in fact, remains unseen. Pasolini is attracted by something that is invisible to the audience’s eye, like god, and the invisible images carry something mysterious.

Another Christ image in a left-wing atheistic context is that of the dead body of Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928 – 67), photographed in 1967 by Freddy Alborta. There were factors to Guevara’s image that lent themselves to comparison with the figure of Christ descended from the cross. He was in his thirties when he died, had long hair and a beard and he gave his life as a martyr in the cause of the dispossessed poor in a deeply Catholic country. Guevara was executed on the orders of the Bolivian president in 1967 after he failed to instigate a revolution in Bolivia.

The British leftist art historian of the 1960s and 1970s John Berger referred to this particular photograph of Guevara as an iconic image of both the revolutionary hero himself and of the political forces that he represented. According to Berger in “Che Guevara: The Moral Factor,” it located the figure of the dead Guevara within a Christology of redemption by martyrdom (202-8).

After his execution, Guevara’s body had been flown to Vallegrande where he was photographed lying on a concrete slab in a laundry room. Hundreds of the local people filed past the dead body in tears, regarding it as Christ-like in its martyrdom. Berger considered that this photograph resembled two paintings of outstanding historical importance, namely, Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, Mauritshuis, The Hague (1632) and Mantegna’s Lamentation.

As in Pasolini’s radical political filmic critique and in Alborta’s photograph, Christology has been lifted out of the bounds of institutional church dogma, floating free in the perception of the congregation, of the audience for the ritual performance of the Church and hence no longer institutionalized and Catholic in a confessional sense, but only in a generic one. Is this still a Christian/ Catholic image?

Yes, intensely so, despite it floating free from its original context. The Catholic trace remains and if that trace is not perceived as being Catholic, then the image makes no sense, it cannot be read and it cannot speak. Freddy Alborta, decades later, admitted that he had been very aware that he was in the presence of a legendary Christ figure (202-8)

In the traditional genre of the artist’s self-portrait, the imitation of the image of Christ is rare. There exists Albrecht Durer’s Self—Portrait, Alte Pinkothek, Munich (1500) and, for example, in modern Polish art there is the work of Jacek Malszewski which involves an ironic questioning of both of his own self-identity and of Poland as the “Christ of nations,” according to Irena Kossowska in Symbolism in Polish Painting at the Turn of the 19th and 20th Centuries.

In contemporary Polish art, there has emerged recently a unique class of work in the mode of self-portraiture made by Krzysztof Gliszczyński (b. 1962), established Polish artist and professor of painting at the Akademia Sztuki in Gdańsk

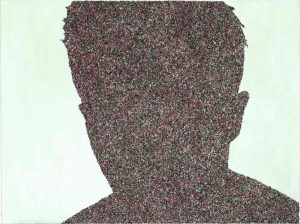

Gliszczyński’s art is an instrument for investigating the painful borders between life and death, memory and forgetting, gain and loss, history and its obscuration in a subtle investigation into the issues of post-war and post-communist Polish national and his own personal identity as a Pomeranian Pole. He deliberates how individual subjectivity is generated through the interaction between personal memory and collective political history, as reflected in his recent series of self-portraits from 2007. (Fig.1)

To address these problems of national and individual identity, Gliszczyński has adopted the theoretical model of Hannah Arendt concerning the retrieval of fragments of history lost in the fracturing of historical continuity by fascist and Stalinist regimes.

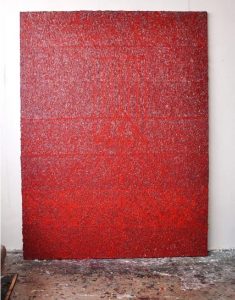

For example, in The Mythology of Red Gliszczyński ritually processes and re-processes the physical materials of his constructions, never entirely destroying them. He creates a dense surface of jagged marks meticulously created from the impression of his fingernail, a visceral response to his meditations on history as collective and individual memory. These marks of his fingernail take the form, deliberately of a cross form and it is a subdued and subversive Christological reference (Alchemy in Contemporary Art (185-90). These works have been re-exhibited in a recent installation, Iosis (2012) (Fig. 2)

In his conceptual development, since the 1990s Gliszczyński has been investigating the Hermetic tradition, specifically, alchemy, as in his installations, Urny (Urns) (produced in 1998–99). Gliszczyński gathered the residues of dried-up paint from his palettes and paint pots and pressed them into tall glass vessels that recalled alchemical alembics and stills.

Eventually, he eliminated the glass containers and collected the drops of paint that fall onto the studio floor in order to create a free-standing monolith. The urns are funeral urns, a public commemoration of history. (Fig. 3)

Gliszczyński’s work has evolved into a performance aspect, already largely present in his ritualised painting practice. His latest performance work re-enacts the death of Christ, both in the mass and in history, and this sacred sacrifice is re-enacted in Gliszczyński’s performance as the ritualised entombment of the artist himself. In addition, Gliszczyński creates a complex inter-relation between the Christian theology of God the Father and God the Son and himself and his own son.

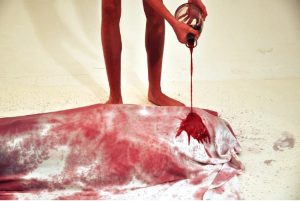

His son embalms the body of his father by pouring wine onto his “shroud.” Into this, also enter further alchemical themes, themselves historically developed from Catholic Christology and Eucharistic doctrines in which the distillation of wine created healing medications. The wine in alchemy is also understood to be the Eucharistic blood of Christ in a chemical form. Initially, Gliszczyński had introduced the theme of alchemical and Eucharistic wine into photographs and paintings and the performance was added only as an after-thought. (Fig. 4)

In his earlier paintings, in works such as Levitation (2002), his own recumbent form had already appeared as in the pose of the Dead Christ, although Gliszczyński, in fact, was not aware of the existence of Holbein’s painting even during his recent performance. In the performance work Gliszczyński’s body becomes a canvas which is painted by the action of pouring on of wine. (Fig. 5, 6)

This theatre of the shroud and the oblations of wine were intentionally referential to Christian dogma and Gliszczyński was at this stage only subconsciously, half-aware, of this Christological context. In fact, at first the shroud was thrown into a rubbish bin, but then retrieved after some further consideration. Gliszczyński has not placed the original shroud on public exhibition, only the photograph of his own body within the shroud, as well as the performance.

The shroud, however, even in spite of (or maybe because of) its absence, due to public interest has gradually acquired a relic-like status, somewhat like the Shroud of Turin.

What is noteworthy about Gliszczyński’s performance is that it was not a public action. It was filmed and photographed in his studio with only himself, his son and the photographer present. The shroud, folded away after an interior, private action, has since been opened out and has become a public icon. Like the Turin shroud, Gliszczyński’s is a copy of his body, almost a negative impression of his own form and flesh.

The whole issue of Gliszczyński not being entirely aware of the Christological implications of his action, whereas audience and critics read his performance thus, raises important questions concerning the generation of meaning in art. How is this produced? In this case a basically unintentional action, focused largely on alchemical symbology, with less consciousness of the Dead Christ/ Turin shroud context is generating an ever-richer and more complex text in which the video and photographs of the action have become implicated as semiotic devices.

The passivity of the artist is also a recognition of the impasse of art in the present time. The texts and discourses pass through the artist as a transmitter, as a canvas on which time and history paint and draw and inscribe their texts which he transmits. There is a subversive theme, that of the abject… the dead body of the father… in Freud’s and Lacan’s analysis, according to Slavoj Zizek and Willy Apollon and Richard Feldstein (105-7).

This inverts the Christian narrative in which the son is sacrificed to the father. Here the meaning is more confused, the father is sacrificed to himself, the artist to his own art and the theme of martyrdom inevitably returns. No other artist has portrayed himself as being dead and being entombed in Gliszczyński’s manner. There needs to be another action to clarify the meaning of the action and to affect a closure of something that is unfinished. Gliszczyński as an artist remains in the tomb. When will he arise? – and to what?

Urszula Szulakowska has written extensively on the history of art and alchemy from the late medieval period to the modern day. She has published several monographs on the subject. She is an art-historian, art critic and theorist who has lectured at major universities internationally.

Tagged with: A New Spirit in Painting, alchemy, Alchemy in Contemporary Art, avant-garde, Bernard Smith, Death of Christ, Eliphas Levi, Freddy Alborta, Hans Holbein, John Berger, Krzysztof Gliszczyński, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Polish art, Surrealism, Zizek