What Might Burning Man Say To Reflexive Christianity In The West?, Part 2 (John W. Morehead)

The following is the second of a two-part series. The first installment can be found here.

With a basic definition of counterculture, as well as consideration of their oppositional forms of expression and differing types, I now turn to consideration of their significance in relation to Burning Man, as well as Christianity in the West.

Klaus Eder in his discussion mentions a “flowering of counter-culture movements,” and explains this growth by noting that, “[t]he new counter-culture movements are trying to stall and even reverse what they regard as the self-defeating process of modernization”.(21) This is interesting in that the current counterculture movements are reacting against aspects of modernization even as the earlier counterculture movements of the 1960s did before them. Burning Man does this by expressing itself as a combination of Yinger’s counterculture types, including aspects of the “[m]ystical or bohemian search for insight and new experience” and the “[a]ctivist attack on the dominant culture and its institutional expressions”.(95)

But what is the relevance of countercultural considerations to Christianity in the West? If we recall that Christianity began as a counterculture, and as Yinger noted, it became a “target for its own countercultures”,(227) then Burning Man may be considered as a countercultural reaction against various facets of modernity, including Christendom as the dominant religious institution.

One of the shortcomings that Burning Man may be reacting to is Western Christianity’s lack of historical memory regarding its own countercultural origins. As Harvey Cox has stated, “The fact that Christianity has so often in its history become counterrevolutionary betrays a drastic deviation from its sources”. (114)

In my view, one of the reasons why Burning Man is so appealing is that many times the church in the West has failed to present a viable alternative for community life as both an alternative culture and a counterculture. Christianity began as a community that expressed the best of the universal and the particular, that is, Christianity was universal and radically inclusive as an egalitarian community that was unified in Christ across all social, ethnic, racial, and gender distinctions, and yet also particular in demonstrating great flexibility in the contextualized forms it developed in community expressions across cultures through history.

The perception of many observers, such as those in the Burning Man community, is that such a form of community life is missing in Christianity in the West, and as a result they create their own alternatives in the search for something viable and vibrant.

While Christians may be unsettled by the rejection of churches in favor of alternatives like Burning Man, they should engage in careful reflection. Yinger says that, “Today’s counterculturists can be thought of as the shamans of urban society dreaming new dreams, formulating new myths, forging alternative paradigms”.(9) If Christians are uncomfortable with the dreams, myths, and alternative paradigms of Burning Man in regards to society, then it is incumbent upon them to formulate and live out forms of alternative culture and counterculture that captures the imaginations and hearts of these urban shamans.

Festivals and the Church

The second area for ecclesiological reflexivity is festivals and festivity. Festivals present specific challenges to Protestantism. While Roman Catholic and secular scholars have devoted serious attention to festivity, this is not the case with Protestants. Festivals and festivity are not taken seriously either as a cultural phenomenon or as a topic for scholarly exploration by most Protestants, and yet Catholic scholars such as Josef Pieper have argued “that festivals belong by rights among the greatest topics of philosophical discussion”.(Back Cover)

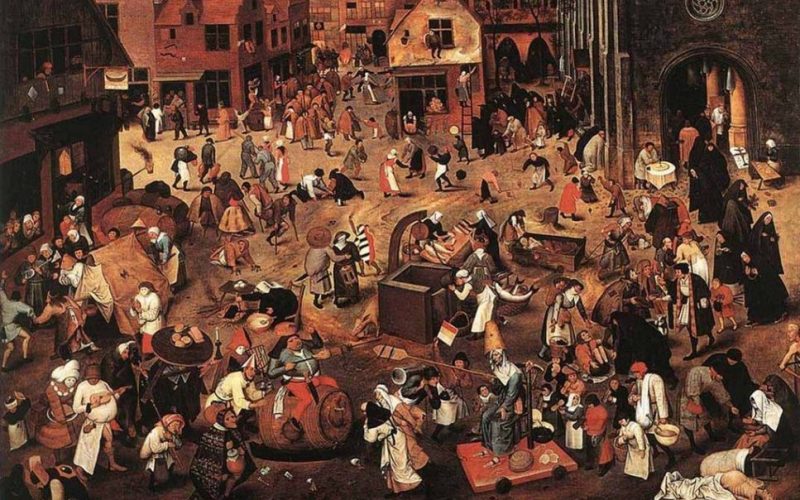

Yinger in his book includes a chapter on symbolic countercultures which use rituals of inversion that reverse and mock the established order. These countercultures have existed in the past and the present, and Yinger says that “such activities can be matched in the medieval and contemporary worlds”.(154)

Peter Burke discusses such phenomena in early modern Europe. He says that, “[c]arnival was, in short, a time of institutionalized disorder, a set of rituals of reversal”.(190) Duvignaud references the same thing in his comment that “festival involves a powerful denial of the established order”(19) In the context of early modern Europe, this celebration of social inversion, according to Burke, involved a number of phenomena, including dressing in costumes, cross-dressing, intense sexual activity, as well as weddings and mock weddings.(186) Burke sees these activities as fulfilling an important social function as ritual regardless of “whether participants are aware of this or not”.(199)

At this point we should note the connection of the festive and ritual expression of acts of social inversion to Burning Man. The activities of social inversion at Burning Man exactly parallel those expressed in carnival and festival in early modern Europe, including costuming, cross-dressing, sexual activity, weddings, and mock weddings. Thus, the activities at Burning Man may be understood as a contemporary expression of festival with historical and cross-cultural precedents.

But an aspect of festival that may not be familiar to Christians is its connection in the past to the life of the church. As Mikhail Bakhtin reminds us, “[a]ll forms of carnival were linked externally to the feasts of the church”.(8) Max Harris notes a similar historic connection between the church and festival and states that, “[a] good case can be made, however, for the argument that Carnival developed within the Christian community from the topsy-turveydom of Christmas”.(140)

Festivals thus have a historic connection to Christianity, both through Christmas celebrations as well as the connection between Carnival and Lent. Carnival is a Roman Catholic celebration with the carnival season being a holiday period that is celebrated during the two weeks before the traditional Christian fasting of Lent. Lent is a time of preparation for Holy Week, and its forty days of observance are symbolic of forty day periods of religious significance found in the Judeo-Christian narrative, most especially Jesus’ retreat into the wilderness for a time of fasting and temptation.

Yet even in its ecclesiastical context the social inversion of festival was still present. Harris notes that carnival celebration in connection with Christmas in medieval and early modern Europe involved “[c]ross-dressing, masking as animals, wafting foul-smelling incense, and electing burlesque bishops, popes, and patriarchs [that] mocked conventional human pretensions”.(140)

If festival was connected at one point in history with the church’s sacred calendar, why did it disappear? At least two reasons seem likely. The first is that such festive play is perceived as dangerous in ecclesiastical contexts. As Frank Manning observes, “[p]lay theology, it seems, is frightened of sensuality, excess and ambiguity which all reside in the body and are unleashed in play process – as if it is frightened of the carnality of birth and death itself”.(369)

Bjorn Krondorfer develops this idea further when he remarks that “play processes (such as dance, festivals or ceremonies) are often excessive, transgressive, inversive and passionate. They can be carnivalesque in structure and ‘anti-theological’…They challenge ‘God, authority and social law’.”(368) A few play theologians such as Jack Santino are aware of the fact that actual play processes, including religious rituals (such as the medieval Feast of Fools), are transgressive, subversive and dangerous; but they do not fully integrate this knowledge in their theological thinking’”. (xvi)

The second reason why festivity has lots its connection to the church and its sacred calendar of celebrations may be connected to the Protestant Reformation. The celebration of certain holidays in the church calendar “diminished in importance” with the Reformation, and further, some seem to have been expunged as a reaction against aspects of Roman Catholicism.

As an example, Ronald Hutton comments on contemporary Protestant concerns over Halloween and its connection to All Saints and All Souls Day from the past:

Such an attitude could be most sympathetically portrayed as a logical development of radical Protestant hostility to the holy days of All Saints and All Souls; having abolished the medieval rites associated with them and attempted to remove the feast altogether, evangelical Protestants are historically quite consistent in trying to eradicate any traditions surviving from them. If so many of those traditions appear now to be divorced from Christianity, this is precisely because of the success of earlier reformers in driving them out of the churches and away from clerics….(384)

I suggest that despite the potential danger that festival celebration poses to the church with all of its rituals of social inversion, that the vacuum created in Western culture as a result of a lack of sacred festivity that includes social inversion has resulted in the creation of new forms of sacred festivity that are interpreted outside the Christian context through alternative cultural events such as Burning Man.

In addition, festivity need not be divorced from the context of Protestant community and church life. Indeed, the rediscovery and experimentation with festivity will play an essential part of the church’s engagement with Burning Man as well as other facets of late modern spirituality. I believe that the church can benefit from fresh exploration of festivity in three areas, that of festivity serving as a reminder of the biblical teaching on social inversion, festivity as a tool for theological reflection, and as a source for fresh ritual in the church.

Utopianism

The final area of consideration for ecclesiological reflexivity is that of utopianism. An analysis of Burning Man reveals that it might be understood as an intentional community that attempts to embody a utopian vision for community.

Adam Seligman defines utopianism as “a state of mind embodied in actual conduct seeking ‘to burst the bounds of an existing order’”.(2) He notes that there “would seem to be some innate connection between utopianism as a mode of thought and social action and the vision of salvation held out by different world-historical religions”.(3)

As Seligman considers various examples of the utopian-salvation vision in world religions he makes the connection to early Christianity in its utopian form of community. He says that, “[o]n the organization level, the original development of Christianity saw the construction of a ‘new moral community’ of believers differentiated from the societies in which they lived and united by bonds of exclusive communal fellowship”.

In his view, the early Christian community and its utopian unity in Christ, drew upon “the Jewish prophetic tradition of the end of days, [and thus] Christianity was itself an attempt to radically alter the social world of late antiquity in line with a vision of a new order, of a new heaven and a new earth”. This utopian community “was symbolized by the Eucharist,” and as an alternative community “[e]arly Christianity thus presented an alternative locus of social identity and of community that was rooted in the experience of grace and the expectation of the Parusia [sic]”. (13)

Seligman’s discussion continues by tracing various historical developments in Christianity’s self-conceptions as a utopian community, and in his view “the major assumptions underlying Christian utopian visions and their realization were radically transformed in the period of the Protestant Reformation”. At the conclusion of his treatment of this issue, Seligman states that, “[w]ith the Reformation, secular callings were given a religious legitimation and were perceived as possible paths to salvation, thus opening up the possibility of a radically new articulation of utopian themes in terms of this-worldly realization of spiritual ends”.(38)

In the challenging post-Christendom environment of the West, the Christian church would do well to rediscover its roots in its earliest expressions as a utopian community and an alternative culture. The first Christians believed that the new creation had already begun through their utopian community, and it provided an attractive alternative for many in the first century.

Burning Man Festival exists as an alternative utopian community in its own right, and one that exists man times in conscious rejection of mainstream institutions, including the Christian church. Given Burning Man’s heterogeneity of “multiple constituencies” with “sometimes conflicting and sometimes complementary readings of the event,” it is perhaps best understood as heterotopic rather than utopic. I suggest that a fresh appropriation of the church’s identity as a utopian community, one that embraces aspects of counterculture, play, and festivity, would provide a much-needed response to the vacuum created by the lack in these areas.

Conclusion

I have argued that the church has much to learn from this intentional community. Carl Starkloff echoes this sentiment in his discussion of liminal and marginalized groups when he states that “their separation from the conventional mainstream can be an occasion for creative reform if the Church will enter into genuine dialogue with these experiences”.(644)

Countercultural considerations, festivals, and utopianism not only represent facets of Burning Man’s success and appeal, but reflection on and engagement with these areas by Christians may also sow some of the seeds for our own revitalization and credibility in the late modern world.

John W. Morehead is a researcher, writer, and speaker in intercultural studies, new religious movements, the biocultural study of religion, intergroup emotions and social psychology in religious intergroup conflict, and multi-faith engagement, as well as theology and popular culture. He is Director of the Evangelical Chapter of the Foundation for Religious Diplomacy (www.EvangelicalFRD.org). He also blogs on religion and cultural studies at Morehead’s Musings and on religion through the fantastic in popular culture at TheoFantastique.

Tagged with: Burning Man, counterculture, cross-dressing, festivals, Frank Manning, Harvey Cox, JesusMax Harris, Josef Pieper, Klaus Elder, Middle Ages, Mikhail Bakhtin, Peter Burke