How Political Art That Works…Works (Margot Mitchell-Nockowitz)

In the 2017 Whitney Museum Biennial, contemporary painter Dana Schutz’s contributing work “Open Casket” (2016) was set to be exhibited for an allotted time of 18 weeks. It was hung with and in between the multimedia works by other artists, all of which were meant to be in a curatorial conversation with each other about what the Whitney describes as the topics of “racial tensions, economic inequities, and polarizing politics” (whitney.org).

The Whitney, and accordingly, Dana Schutz herself, had what some would consider well-meaning intentions with their collective venture into the topic of political strife in what was – at the time and in following months – a divided country fraught with tension and civil unrest proceeding the 2016 election, and its rampant moral division amongst the American people. Dana had painted an abstraction of the infamous and striking photo of 14-year-old Emmett Till, a boy that was lynched in 1955 after being wrongly accused of allegedly whistling at a white woman.

Aside from Schutz, a white artist, the exhibit had many artists of color on display, attempting to uplift and recognize their work handling subject matters that both affect their daily lives and have affected their history as people of color. Among the moderately diverse group of artists included a piece made by painter Henry Taylor, titled “Times Thay Ain’t A-Changin’ Fast Enough!” on an opposite wall to Schutz’s painting that featured an abstraction of the shooting of Philando Castile, a black man killed in his car by police after being pulled over in 2016.

In an editorial piece on Taylor titled “Beer with a Painter”, Hyperallergic noted: “His painting[s] bear [emotional porosity]. His painting world is his personal world, and our shared cultural world.” And stating in another article titled “Violence of The 2017 Whitney Biennial” that Taylor “…does his part by tending to the wound in the best way he knows how…What’s more, by freezing a moment of the raw footage, Taylor is able to plug the incident into a larger system of violence.”

It was similar to Schutz’s piece, in that it was an artistic rendering of a violent act against black men in America, and the abstractions both featured striking colors, strong line work, and hints of conceptualism that spoke to their respective creator’s personal style. However, the two met very different criticisms for their interpretations of what could be considered history-writing murders for the American people.

For Taylor, the reception was celebratory, the piece being added to his prolific line of work dealing with similar subject matter that outlines the heart of modern black American culture. For Dana, the doors of the Whitney burst open with the outrageous force of political dissent. People were not pleased with her.

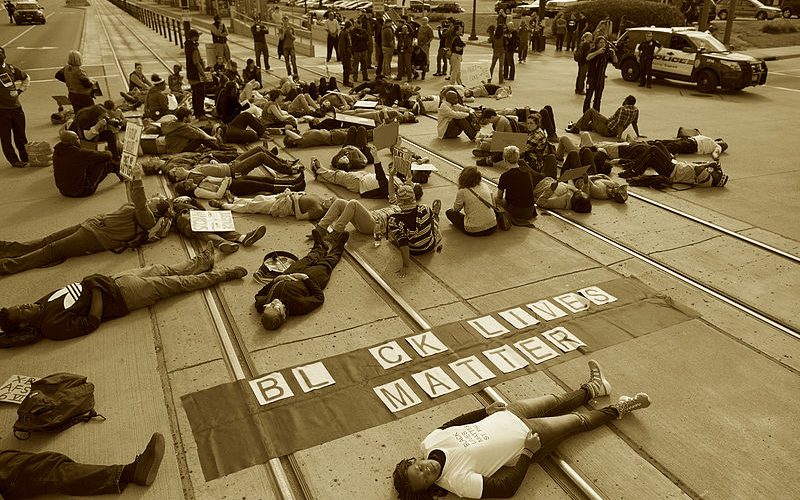

The protests against Dana’s painting echoed perpetually into the chamber of the modern conversation surrounding white commandeering of black narratives, including historic suffering and racist brutality, like the death of Emmett Till. Labels were vocalized, claiming Schutz’s work dripped with performative care and insensitivity for its subject.

Protestors stood in front of the painting taking Instagram photos, creating their own work in response to the trauma it both ignored and perpetuated further, speaking their mind on the validity of the message of the piece as a political work, and dismantling its effectiveness with one clear, collective thesis: “[Dana Schutz] has nothing to say to the Black community about Black trauma.”

At the height of the exhibition’s discord, activist and frontwoman of the protest, Hannah Black, made the following statement about the political implications of Schutz’s work, stating: “…that a ‘painting of a dead Black boy by a white artist’ cannot ‘correctly’ represent white shame; that it’s an example of an unacceptable practice of white artists transmuting black suffering into profit; that white artists who want to be good should not treat black pain as material because it is not their ‘subject matter’; and that Emmett Till’s mother made her son’s dead body ‘available to Black people as an inspiration and warning.’ The mainstream media’s ‘willingness’ to circulate images of black people in distress is equated with public lynching” (Hyperallergic). In the same letter, Black called for the destruction of the painting, to the dismay and disagreement of many artists and political protestors.

The case of Schutz’s “Open Casket” and the 2017 Whitney Biennial is a notable example of a modern phenomenon: the dismantling of the metaphoric hall-pass to simply create “political” art for the purpose of creating it, and the ultimate processional discourse about authorial intent when it comes to art that is subjectively political. People are becoming more decisive and thoughtful towards creators and the sociopolitical implications of the work that they create, as well as the narrowing ability for the viewer to separate the intent of the artist from the art (as theorized by Roland Barthes as the “death of the author”).

This is resulting in a direct correlation between what people mantel as “effective” and what is oppositely “inappropriate” subject matter for a given artist to tackle – which political art works, and which art doesn’t. If the intent of the art is like that of Schutz’s – what the public considers hollow opportunism or mere capitalization off of something that, to the artist, is foreign territory considering their previous work – it is thrown into the bin labelled “ineffective” because of the context rather than the content; al-though, it has been argued the technical interpretation of Schutz’s work is also disrespectful and poorly rendered.

The idea that objects to the previous notion that anyone can make anything political at any time is being challenged, and so the question must be raised: How does one artist orchestrate pitch perfect harmony between themselves, subject matter, and execution, in order to create acceptable, effective political art, and also, how can we effectively render subject matter that exists outside of our available and limited individual life experiences?

The answer has two parts: consideration for the subject matter the artist and subsequently the art are hoping to represent, and accessibility. The first half of the answer, intentionality, can be generally defined by how reflective the art is to and of the conversation being had between those affected by the topic it is addressing.

There is an array – one could consider it a plethora – of examples of effective, political artists and artworks that have been created as a result of the public’s close examination of authorial intent, and the introspective nature it requires from an artist. Some consider this part censorship, others consider it being more sensitive to subject matter as not to perpetuate negative representation in media.

Artists and collaborators S.A. Bachman and Neda Maridpour consider it a priority to the functionality of their work as meaningful, active, political art. They are the creators of “Women On The Move,” an organization stemmed from their work titled “Louder Than Words” that deals with “looking beyond the whiteness” in the conversation surrounding sexual assault and gender inequality in America.

Women on the Move is a literal movement – all of the information they’ve gathered on the project’s topic having been packed into a truck that travels state to state, stopping to have discussions with people directly affected by the intertwined traumas of racism and misogyny. They want people to talk, not only to them, but to each other, about the information they are receiving because of the truck and how it relates to their interpersonal experiences.

Bachman and Maridpour describe the intentions of the work in an article by Sia Nyorkor, in which Bachman says, “People like to shy away from [topics of gender and race in-equality that are] still seen as taboo in some ways and so we have to try to get people to feel more comfortable talking about these issues,”, and Maridpour follows: “I think the term whiteness is a sensitive term and people often become defensive about some of these conversations. What we are actually looking for is that kind of question that would bring people to us [so] that we could start a conversation about this.”

In other words, their art quite literally follows the issue its addressing, and at the same time, the artists and the art itself become open forums for communities that need discussion-based stimulation, the thing that Bachman and Maridpour initiate with the methodology of conferences and discussions that are free to attend. These factors, mixed with their insistence to aid discussion that trumps their desire to self martyr or expel their personal guilt, combine to make a result of definitively effective political art. It’s considerate, it’s available to the public, and most importantly, it shows almost immediate results for its intentions.

The second half of the equation of effectivity is accessibility. A great example of this (and one that also shows a lot of contextual consideration) is Liz Glynn’s recent public exhibit “Open House”. ) In an article by the Boston Globe written about the exhibition titled “A new public art installation puts the ruins of a Gilded Age ballroom by Kenmore Square”, Glynn talks about the pieces’ execution. The work, “26 pieces — visually attractive and stone-hard — [that have the] look of sculpted clay, with an overcast hue and naturalistic floral motifs”, are a commentary on spaces that are owned and in turn privatized by the upper class.

The clay pieces were placed in a public park, a space that is often also privatized and exclusive towards unwanted individuals, despite the claim that parks are democratized. Anyone that enters the public park space is invited to interact with the art, which is manufactured, Guilded Age specific furniture, by sitting on it. This is work that uses the issue it is addressing – privatization and class division – and brings the solution to the public in a clever and historically considerate way.

Glynn herself, a Los Angeles-based conceptual artist, may not have ever dealt with the consequences of privatization of seemingly public spaces, but she is creating work about the subject that is nonexclusive, that is accessible and inviting to the people whom the problem effects in a real way. Glynn addresses this decision eloquently, saying, “We have hit, in the last couple of years, heights of income inequality not seen since the Gilded Age…Generally, thinking about the collective social responsibility in the wealthiest country in the world, the standard for the average should reflect that.”

It is not in all ways necessary for political art to be interactive in order for it to be successful, but there is an idea that threads itself in between these two counterexamples that opposes the downfalls of Schutz’s “Open Casket”. The thread is the acknowledgement that although political art can be self-reflective (Schutz having compared the grief of Till’s mother, Mamie Till, to grief that she would feel for her own brutalized children if they had switched positions), because of the nature of politics and its inability to result in isolated consequences, then in art, the whole must also be considered in favor of the artist alone.

To phrase it differently, the art must be executed by the artist in the same way that politics is by the politician. Neither can exclusively be personal conquests, and neither can be separated from authoritative intention, because there are too many people affected by the perpetuating nature of both to allow for frivolity in motive and implementation. The audience is asking for the artist to care, to really care, about the message and execution of their work, just as they would the motivations of their politicians in respect to the progression of the country and those that shape it.

Margot Mitchell-Nockowitz is a freelance writer and photographer living in Boston, Massachusetts.

Tagged with: Black Lives Matter, Dana Schutz, Hannah Black, Heny Taylor, Neda Maridpour, Philando Castile, Whitney Biennial, Women on the Move