Duchamp – A Liberating Lineage For Social Art Practice, Part 1 (Jacquelynn Baas)

The following is the first of a two-part series.

My thanks to curator Mary Jane Jacob and artist Ernesto Pujol for their skillful editing of this text. Pujol originally proposed the topic of the essay, which will be published in 2018 as part of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Chicago Social Practice History Series distributed by the University of Chicago Press. It is currently posted on https://berkeley.academia.edu/JacquelynnBaas.

Jordan Simmons: One of my old teachers used to say, everybody wants to be good; but if you want to be good too much, it doesn’t work. If I apply that to engaged art, when we tell the students to “let go,” it doesn’t mean let go; it means, go someplace. We are trying to accomplish something…

Joanna Macy: But the accomplishment is not an accomplishment that’s driven by the purpose of consciousness. You know by what it’s driven? It’s driven by the root chakra. It’s driven by Eros. And we have come to such a point of being scared and cowed and robotized by this civilization that we can’t even hear our own erotic drive anymore. And that’s what needs to be liberated. It’s a radically extended sense of self-interest. We’re waking up: if the planet goes, or even if this ecosystem goes, I go with it. So the trees in the Amazon are part of my body. It’s not moral at all; it’s not a question of sermonizing. It’s a question of an expanded erotic connection and an extended sense of self-interest. When that’s tapped, you get incredible energy coming out, and spontaneity, poetry, and laughter.

This conversation between Jordan Simmons, Artistic Director of the East Bay Center for the Performing Arts in Richmond, California, and Joanna Macy, Engaged Buddhist teacher and author, poses energetic engagement with the world as essential to what Simmons calls “going someplace” with art. Macy’s root chakra refers to Shakti: primordial cosmic energy in the Hindu tradition (from Sanskrit shak, “to be able”).

Like Taoist and Mahayana Buddhist practices, many Hindu traditions and practices are based on an understanding of the cosmos as the product of an ongoing, generative interplay between two opposites: the powerful, purposeful “male” principle, and the dynamic, creative “female” principle. The motivating force behind this energetic interaction, and the prime motivating force of the universe, is the creative, enabling power of attraction.

Taoist nei-tan (aka internal alchemy) and Indo-Tibetan tantra yoga were designed to transform erotic energy into mental and spiritual liberation within a system of micro- and macrocosmic relationships. This inclusive, liberated way of experiencing the world is, according to Macy, essential to effective social art practice—art that aims to transform social, political, and ecological realities.

A decade or so before social practice began emerging in the realm of art, a new form of non-sectarian Buddhist practice surfaced in Asia. Engaged Buddhism did not begin as a centralized movement, but was a response to various crises—social, economic, political, and ecological—facing Asian countries as a result of the Second World War and subsequent wars and colonial confrontations. Founded on Buddhist philosophy and values, socially engaged Buddhism was also inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s spiritually based, nonviolent leadership in South Africa and India.

In her book Socially Engaged Buddhism, Sallie B. King describes how in Buddhist Asia long-term social ills became crises during the course of the twentieth century.

If Buddhism had nothing to say about and did nothing in response to crises, challenges, and problems of this magnitude, it would have become so irrelevant to the lives of the people that it would have little excuse for existing, other than perhaps to patch up people’s psychological and spiritual wounds and send them back out into the fray. … Fortunately a generation of creative, charismatic, and courageous leaders emerged throughout Buddhist Asia in the latter half of the twentieth century, responding to these crises in ways that were new and yet resonant with tradition. (3)

Something similar might be said of art: if in response to the widespread social upheavals of the 1960s artists had remained above the fray, art would have become irrelevant. Fortunately, a new generation of artists committed to social reconciliation and change emerged to protest and help remedy injustice.

In Buddhism, lineage indicates a line of transmission of knowledge and practice going back to the historical Buddha. Art too has its lineages. In Asia, socially engaged Buddhism would have provided a relevant model. In the West, social art practice surfaced in the years surrounding the student uprisings of 1968, and its lineage would not at first appear to go back much earlier than that. Its origins are usually traced to the Situationist International of 1957- 72—an international organization of social activists made up of artists, intellectuals, and political theorists—and the even more international Fluxus network of artists, musicians, and designers active during the 1960s and 70s.

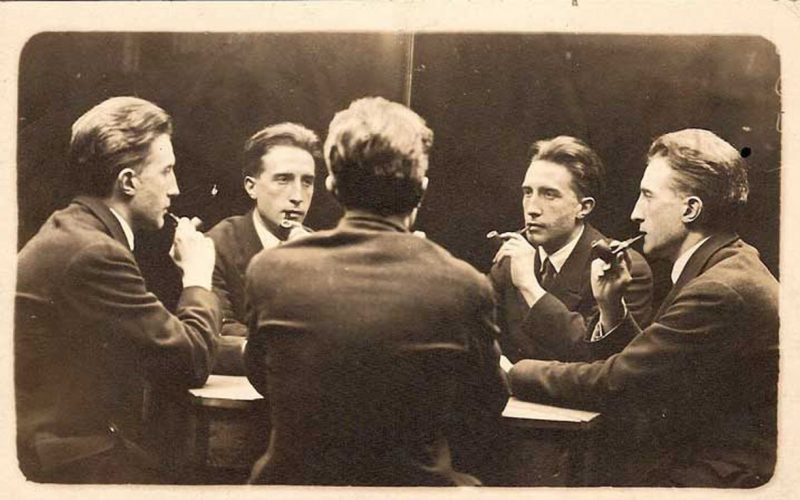

Tracing the social art practice lineage further back, the early twentieth-century avant- garde Dada movement is generally understood to have inspired both the Situationists and Fluxus. Dada progenitor Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) thus emerges as perhaps the most important ancestor in a liberated lineage for social art practice. Interestingly, Duchamp turns out to be at least as relevant to artists in Asia as he is in Europe and the Americas. The reason, I suggest, is that Asian artists are generally more culturally grounded in the worldview that Duchamp had to work to achieve. They seem more easily to understand the Duchamp who realized the modernist goal of removing the barrier between art and life. When asked toward the end of his life what his greatest achievement was, Duchamp said,

Using painting, using art, to create a modus vivendi, a way of understanding life; … trying to make my life into a work of art itself, instead of spending my life creating works of art in the form of paintings or sculptures. I now believe that you can quite readily treat your life, the way you breathe, act, interact with other people, as a picture, a tableau vivant or a film scene, so to speak. These are my conclusions now: I never set out to do this when I was twenty or fifteen, but I realize, after many years, that this was fundamentally what I was aiming to do.

Duchamp’s New York gallerists Harriet and Sidney Janis wrote of him in 1945:

He identifies the means of working, the creative enterprise, with life itself, considers it to be as necessary to life as breathing, synonymous with the process of living. … Merging the impulse of procreation with that of artistic creation, there apparently accrues for Duchamp a sense of universal reality which interpenetrates the daily routine of living. (311)

According to the Janises, Duchamp’s concept of the art of life had two aspects: identification of the artistic impulse with the erotic impulse, and a resulting sense of universal reality interpenetrating daily life. Eros is one of the qualities that distinguishes Asian from modern western forms of spirituality. “I believe in eroticism a lot,” Duchamp commented, “because it’s truly a rather widespread thing throughout the world…Eroticism was a theme, even an ‘ism’ which was the basis of everything I was doing at the time of the Large Glass.” (88)

The precise connections between Asian perspectives on reality and the work of Marcel Duchamp are too complex to analyze here. Yet based on his artworks and some of the things he said, it seems clear that Duchamp drew on Asian philosophies and practices to develop a liberating art praxis fueled by the power of erotic attraction.

“The word ‘art’ interests me very much,” Duchamp said. “If it comes from Sanskrit, as I’ve heard, it signifies ‘making’. (16)” He was probably referring to the ancient Indo-European root, ar, which meant to join or fit. It is the root of the Sanskrit word, ara (254), which signifies the spoke or radius of a wheel (among other things).

In Buddhism, the wheel is associated with the Wheel of the Dharma, the legendary wheel the Buddha drew on the ground when he preached his first sermon, “Setting in Motion the Wheel of the Dharma.” That wheel stood for a number of things, including the newly enlightened Buddha’s determination to begin his missionary task of turning the wheel of truth in this world. Duchamp said that his Bicycle Wheel, which he made in 1913 by attaching a wheel to a stool, was for his own personal use and was not intended to be a work of art.

Duchamp’s reference to Sanskrit suggests that Asian perspectives on reality influenced his thinking about art. He used a Sanskrit prefix to try and explain to artist Richard Hamilton what was wrong with labeling neo-Dada artists “anti-artists”:

An atheist is just as…religious…as the believer is, and an “anti-artist” is just as much of an artist as the other artist. “Anartist” would be much better. … “a, n”-artist, meaning, “no artist at all.” That would be my conception.

The Sanskrit prefix “an,” meaning “not” or “non-,” becomes “a” or “un” in English. An anartist is an unartist. But Duchamp didn’t say “unartist” or “a-artist,” which is how Hamilton wrongly repeated Duchamp’s neologism. The more culturally specific “anartist” parallels the Buddhist concept of anatman, or “nonself,” in contrast with Hinduism’s atman, or enduring soul. At the same time, anatman counters the belief in annihilation of the self—which, the Buddha pointed out, presupposes the existence of a separate self to be annihilated. Anatman is no self at all, just as anartist is no artist at all. Marcel Duchamp didn’t believe in “art,” but he did believe in the artist—more accurately the anartist, whose art is the art of life.

During the First World War the anarchist antics of Dada artists, with Marcel Duchamp as their éminence grise, had already taken art in a socially resonant direction. For Duchamp, Dada was a fiercely compassionate response to World War I: “We saw the stupidity of the war,” he told an interviewer. “We were in a position to judge the results, which were no results at all.

Our movement was another form of pacifist demonstration. (670)” Guillaume Apollinaire predicted as much in his 1912 book, The Cubist Painters, where he concluded his short essay on Duchamp with a prediction: “It will perhaps fall to an artist as disengaged from aesthetic considerations and as concerned with energy as Marcel Duchamp to reconcile Art and the People.”

Apollinaire’s prediction has tended to mystify art historians and critics: Duchamp is generally considered too esoteric an artist to have concerned himself with social reality. Indeed, when asked about it later, Duchamp refused to endorse Apollinaire’s claim: “Nothing could have given him the basis for writing such a sentence,” Duchamp told an interviewer. “Let’s say that he sometimes guessed what I was going to do, but ‘to reconcile Art and the People,’ what a joke! (37-38)”

However, in that very same interview Duchamp indirectly sanctioned Apollinaire’s prediction by insisting that art be allowed to play a social role: “Since Courbet, it’s been believed that painting is addressed to the retina; that was everyone’s error. … Before, painting had other functions: it could be religious, philosophical, moral. … It has to change; it hasn’t always been like this. (43)” Substitute “art” for “painting” (which is what he meant), and Duchamp would seem to be saying that art once had a social function and ought to again.

Did Duchamp think of his art as playing a social role? Consider The Small Glass, which Duchamp referred to as a “voyage sculpture. (59)” It was made during his stay in Argentina, where he and his friends Suzanne Crotti and Katherine Dreier had gone in 1918 in order to get as far as possible from the ambience of World War I. The French word voyage means what it does in English: “travel, journey, sojourn.” Travel often helps to provide perspective on a situation; the French word voyant means not “traveler,” but “seer,” “clairvoyant.” Duchamp hung his glass voyage sculpture on Dreier’s balcony overlooking Buenos Aires and photographed the nighttime city through it, thus providing perspective from the southern hemisphere onto a war-torn world.

Inscribed on this work like a set of instructions is: A regarder (l’autre côté du verre) d’un oeil, de près, pendant presque une heure, which has traditionally been translated, “To Be Looked At (From the Other Side of the Glass) With One Eye, Close To, For Almost an Hour.” A more literal translation reads, “To look at (the other side of the glass) from one eye, up close, for almost an hour.” Though the differences are slight, the second version implies not only viewer- participation, but that what is to be looked at for such a long time is not the work itself, but the world on the other side of the glass.

The focal point of The Small Glass is a convex lens. At normal viewing distance, everything appears through Duchamp’s magnifying lens upside down. Up close, on the other hand, it all becomes a homogeneous blur—the way the world looks to a newborn, or to someone born blind whose sight has been suddenly restored. As Duchamp told his first wife, Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor: “You have to try to see everything as if for the first time, all the time. (48)”

To Be Looked At is among other things a meditation device that offers access to the world as it first appeared: an interwoven, constantly moving tapestry of colors. In this higher- dimensional vision, objects lose their separate identities—you might say their separate selves— and merge into a single, continuous Self. What the outcome of contemplating such a world for almost an hour might be, I’ll leave for the reader to discover. (To Be Looked At is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.)

Back in 1913 Duchamp dabbed two little “lights” in gouache, one red, the other green (or yellow), onto three identical commercial prints of a winter landscape that he inscribed, “Pharmacie.” Only one has survived, but he made replicas for The Box in a Valise (1941) and View magazine (1945). “I saw that landscape in the dark from the train,” Duchamp recalled, “and in the dark, at the horizon, there were some lights, because the houses were lit, and that gave me the idea of making those two lights of different colors … to become a pharmacy; or at least they gave me the idea of a pharmacy, there on the train. (597)” Duchamp’s idea of a pharmacy referred to the jewel-like glass vessels filled with colored water hung outside of pharmacies to alert passers-by that aid was available within.

Pharmacy is not the only work that indicates Duchamp thought of art as a kind of cure. In 1922 he wrote his Dada colleague Tristan Tzara to propose they produce a multiple consisting of four cast letters, “D, A, D, A,” strung together on a chain and sold with what Duchamp described as,

A fairly short prospectus…[where] we would enumerate the virtues of Dada. So that ordinary people from every land will buy it, we’d price it at a dollar, or the equivalent in other currencies. The act of buying this insignia will consecrate the buyer as Dada. … [It] would protect against certain maladies, against life’s multiple anxieties, something like those Little Pink Pills for everything …You get my idea: nothing “literary,” “artistic”; just straight medicine, universal panacea, fetish—in the sense that if you have a toothache you can go to your dentist and ask him if he is Dada. (238)

From his dentist example, Duchamp’s “Dada” would seem to be someone who can give you relief.

The Sanskrit word Dadati means “Giver.” One of the Sanskrit names for Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, is Abhayam-dada (123f), with Dada—“giver”— appended to abhayam, which means “fearless.” So the bodhisattva of compassion is “the giver of fearlessness,” a trait that would be as helpful in an artist as in a dentist. One way to understand Duchamp’s proposed Dada “fetish” is as a variation on Pharmacy’s alert to the universal panacea art can offer.

There is evidence Duchamp also liked to think of his optical works in terms of humanitarian service. About his 1935 Rotoreliefs, Duchamp told Calvin Tomkins: “I showed these things to a sort of scientist, an optics physicist. He said, yes, this is very interesting because we have special designs to bring back the feeling of the third dimension through [sic] one- eyed men. … Of course there was no interest in the artistic world, but for me it was very important.” (206)

Many of these one-eyed men would have been war veterans. Duchamp, who in 1918 had a part as a film extra playing a blinded soldier (206), clearly liked thinking of his Rotoreliefs as therapy for the traumatized and wounded.

In 1942 Duchamp designed the catalogue for First Papers of Surrealism, the wartime exhibition in New York where he installed Sixteen Miles of String (171f). For the publication, Duchamp and his co-organizer André Breton proposed that artists choose a “compensation portrait” to represent themselves. Duchamp chose a photograph of an emaciated, careworn woman taken by Ben Shahn while working for the Farm Security Administration.

While her face does superficially resemble Duchamp’s, it is hard, intellectually and emotionally, to reconcile this tragic image with its caption: “Marcel Duchamp.” There is a Shinto saying, “The heart of the person before you is a mirror; see there your own form.” I suggest Duchamp saw in this woman’s visage not only someone who looked like him, but someone who was him. For Duchamp, “compensation” would have signified a compassionate mental practice: Étant donnés—“Given”—was the title of his last major work.

The following year Duchamp submitted a collage entitled Allégorie de genre for the cover of a patriotic Americana issue of Vogue magazine. “I made a George Washington in the geographical shape of the United States,” Duchamp said later. “In place of his face, I put the American flag. It seems that my red stripes looked like dripping blood. (85)” What Duchamp described as “red stripes” were made not with paint, but with iodine, on white gauze that he fastened down with thirteen star-headed nails. The effect is nothing if not visceral. (Vogue rejected Duchamp’s design, but André Breton published it in VVV later that same year.)

The ability to see Allégorie de genre as simultaneously the bloodied head of George Washington and a blood-drenched map of the United States is the result of an optical illusion known as spontaneous morphing (95-96). Duchamp’s example challenges us to grant our perception ninety degrees of flexibility and see both images at once. His title translates literally as “Genre Allegory”—an oxymoron, since genre art straightforwardly depicts everyday life, while allegory contains hidden moral, historical, or political meaning.

A more imaginative reading of Allégorie de genre combines sounding-out and translation to read: “all the gory of [our] kind,” with “gory” ironically eliding glory and bloodshed. A fierce critique with an equally fierce undertone of compassion, Allégorie de genre uncannily manages to be both pacifist and patriotic. One of the things Duchamp is gently prodding us toward here is a both/and dimensionality in our habits of perception, including our perceptions of history and of human nature.

Jacquelynn Baas is an independent curator, cultural historian, writer, and Director Emeritus of the University of California Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. She has published on topics ranging from the history of the print media to Mexican muralism to Fluxus to Asian philosophies and practices as resources for European and American artists.

Tagged with: Calvin Tompkins, Harriet Janis, Mahayana Buddhism, Marcel Duchamp, Sallie King, Taoism, Trista Tzara