But Is It Art? – Searching For Simple, Practical, And Illuminating Answers, Part 2 (Jakob Zaaiman)

The following is a second installment of a two-part series. The first part can be found here.

The question then arises, how does the “theatrical pretense” – and its invitation to a theatrical narrative – relate to inanimate crafted objects such as paintings, or sculptures? The answer is that, in the hands of an artist, paintings, and sculptures, and found objects, and readymades, become, as it were, theatrical props and lobby cards, referring to a larger, more encompassing narrative which may or may not be immediately apparent, depending on the way the artist has chosen to orchestrate it, and the extent to which the onlooker has informed themselves.

Beuy’s “Fat Chair”

For example, the many bits of random and loosely connected junk that Joseph Beuys presented as artworks make almost no sense on their own, despite Beuys’s own often lucid accounts of what they are supposed to mean, but taken collectively they amount to a fascinating unfolding narrative centered on Beuys himself, combining autobiography, fictional biography, Beuys’s mentality, strange extremist performance, and all kinds of other attributes. As a possible sculpture, a triangular wodge of animal fat covering the seat of a readymade wooden chair doesn’t make much classical aesthetic sense – especially as the fat eventually decomposed to nothing – but as a calling card for the Beuys world, it is as powerful as any theatrical gesture could possibly be. Fat Chair (1964-1985) invites you to join the Beuys narrative, then it is up to you to take it further.

Consider this proposition: the “fat chair” is theatrical prop from Beuys’s mysterious, unfathomable world, not a metaphor for anything? True enough. “Art” narratives are not all that easy to discern – some are deeply buried – and this is why many people fail to pick up on them, preferring instead to go for “symbols”. So if Beuys’s artworks are viewed as if they are standalone objects, they will require interpretation, and this invariably involves looking for metaphors, and other forms of allegory. Art then becomes a matter of symbology and systematic decoding.

Of course this can be enjoyable in a crosswordy type of way, but it’s a trivial activity when compared with the immersive experience that goes with viewing art as the taking on of an entire perspective. Beuys’s Fat Chair is not a mere metaphor for human corporeality – or some such feeble reading – it’s a movie still, a lobby card, a theatrical prop – inviting you to Beuys’s strange and disturbing film concret (Film concret – as a distant relative of musique concrète – is meant to represent something like a special kind of avant-garde narrative medium, subtle, unsettling, and ultimately unfathomable”).

But how exactly do you discern an art narrative such as the one orchestrated by Beuys? How do you “get” what he is saying ? You have to start by familiarizing yourself with an artist’s oeuvre as a whole, sifting through the clues, and combining it with whatever contextual information seems to be relevant, and then letting the central narrative reveal itself of its own accord. This is not as difficult or demanding as it may seem, if you are prepared to put in the legwork. It is simply a matter of looking beyond the individual artworks for something which might meaningfully constitute a broader narrative – an encompassing vision, if you like – which would then make sense of what might otherwise look to be rather underpowered items on their own. Reproductions of Brillo boxes and Coke bottles and soup cans don’t have much to say by way of classical aesthetics, but they come into their own as calling cards to the Warhol world. It’s the Warhol world which is Warhol’s real “art”, not the individual artworks – the Coke bottles, soup cans, screen prints, and the rest – which only derive their meaning from the narrative world they refer to, and are an essential part of that world.

And as with anything based on ethereal intuitions and meetings of minds, we can never be certain about the narrative we discover, especially if they are characteristically mystifying. All one can do is assess the evidence, and go from there. Interpreting Beuys’s artworks one at a time as modern day allegories is a tedious and disheartening affair, as it tends to be powered by a sense that his whole project was really just a student jape, and that if he’d only be able to paint like an old master we wouldn’t have to put up with all this nonsense in the first place.

But if you join him in his theatrical production, and come to see how all his works are part of a mysterious narrative environment, and that the central narrative is as essentially strange and indecipherable and provocative as only the most fascinating narratives can be, then you get what his art is all about. His “art” is not a collection of desultory readymades and found objects, combined with bizarre performances, meaningless drawings, and absurd manifestoes: it is the Beuys world itself, presented to us through various media, with all the individual artworks merely items of artistic stagecraft.

However, just because we have redefined modern contemporary artworks as narrative props doesn’t mean that one can’t enjoy them aesthetically as objects in their own right. Of course one can, although the aesthetic impacts one will encounter are unlikely to bear much relation to those of classical fine art. One can develop an aesthetic taste for anything, given that any object can always be abstracted from a given context and contemplated for its aesthetic features alone, but the point is that when it comes to items of modern contemporary art, the aesthetics of the artwork are very much secondary to its place in a greater theatrical narrative, and that insofar as the artwork can be seen to derive its meaning from a greater narrative, its aesthetics are almost unimportant. These works are not meant to be objects of classical fine art, they are meant to be part of a modern narrative environment.

If Beuys’s peculiar sculptures, and installations, and performances, and drawings, and general detritus come together as “art”, then doesn’t this make modern contemporary art a complete free-for-all, allowing anyone to exhibit anything for any reason? How do we tell the difference between one thing and another? How do we judge the good from the bad?

It is not the presence of a narrative alone which certifies art. After all, anything and everything can, with a modicum of effort, be made to generate some sort of narrative, however flimsy. What makes “art” distinctly itself is the presence of a ‘strange and disturbing’ narrative; a storyline which, subtly or harshly, openly or insidiously, will unsettle us, and rattle our cage. Normality – even in its guise of the extraordinary and the unusual and the astonishing – is addressed by ordinary crafted narrative, and this category of narrative works ultimately to reassure, with the obligatory happy ending. Art is of an altogether different order.

From “Not Art ” To “Not Yet Art”? -Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst

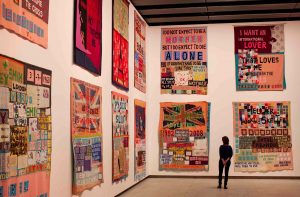

We can see this if we look at the work of “artists” who, for whatever reason, fail to access the strange and disturbing. They may not even be particularly interested in doing so. Tracey Emin, for example, is very much engaged in employing crafted objects – installations, sculptures – in the service of her theatrical narrative, but this narrative, though sensational and lascivious, has nothing unsettling about it from any angle.

It is straightforwardly confessional in the manner of a clinical ‘case study’, with every prop – whether a neon sculpture or a piece of writing or a patchwork quilt – deriving its meaning entirely from its relation to Emin’s narrative persona, which itself is a variation on the reassuringly normal. There is nothing strange about extremes of expression. This is not to denigrate her craft – her single-minded self-promotion – which is as unquestionably effective as it is successful; it is simply to say that none of what she does qualifies, by our definition, as “art”.

Damien Hirst is a more complex and interesting figure when it comes to deciding whether or not his work is “art”. Some of his pieces could be described as unsettling, but all the contextual evidence tends to dispel that impression, and make us think that he is simply a canny, calculating sensationalist. Once again, this is not a value judgement, merely a definitional one, concerned only to identify a very specific kind of narrative. Hirst has been successful in publicizing his wares, but the many and various images, unlike those produced by Jeff Koons, are not held together by some kind of disquieting thread, and so as a totality they lack a compelling core.

Some of Koons’s imagery is of a piece with Hirst’s, but what underpins it and validates it as authentic “art” is its militant soullessness and relentless emptiness, echoing the defiant superficiality of Andy Warhol. Everything about the Koons world – his persona and his artworks – is wholly congruent with itself, and it’s impossible to detect the merest crack, the slightest moment of existential uncertainty, in his presentational edifice. Koons incarnates, through everything he does, says, or makes, a world of deeply disturbing refulgent vacuity. Not so Hirst; there is something unconvincing about him, something a little too calculating and opportunistic – in the wrong way – and this destroys the narrative cogency of his work.

Aesthetic craft is designed to achieve a positive sensorial effect – an impact – generally categorized under the concept of “beauty”. Appreciating aesthetic craft involves concentrating solely on the interplay between the sensorial attributes of an object, irrespective of any purpose or utilitarian function it may have. Classical fine art – properly classical fine craft – of the sort to be found in museums and national galleries is the representative template for this kind of work.

Art, on the other hand, is all about exploring the strange and disturbing; and artists create, through their works, an unfolding narrative. This is orchestrated theatrically, very much like a film, so that individual artworks are not standalone objects but rather items which contribute to a larger landscape – a dispersed stage set, if you like – from which they then derive their meaning.

But it needs to be underlined – in case anyone was wondering – that only a fraction of the strivings taking place under the banner of modern contemporary art even remotely qualify as strange and disturbing, which means that much of what masquerades as art is not art at all, but merely crafted material of one sort or another. Happily enough for the cogency of our case, many of the most famous names in modern art – Warhol, Beuys, Duchamp, Gilbert & George, Koons, Francis Bacon, Lichtenstein, Kiefer, Rego, Cindy Sherman – benefit greatly from being understood as connoisseurs of the dark and disturbing, even in those instances where – like Warhol or Koons – they might declare themselves to be heading in quite the opposite direction.

The “But Is It Art?’” Query

Having offered a very general but practical definition of “art”, we can now return to the original question, in order to show both how it can be answered, and how it testifies to an ongoing confusion as to art’s true nature. When people ask the question ‘But is it art ?’, they are invariably perplexed by a modern contemporary artwork – probably a readymade, or a bizarre performance, or an inexplicable video – and wanting to know if it is worthy of being considered “art” alongside works of a more classical nature. They are hoping for some convincing conceptual guidelines that will make sense of what appears to them to be so far removed from a normal understanding of art as to be impossible to judge.

We have seen that “art” used to be about “classical fine art”, of the sort you found in art museums. Then something new emerged in the late 19th century, which opened up a division between classical standards and modern possibilities, resulting ultimately in a separation between sensorial aesthetics – properly the realm of craft – and theatrically-based art, with its rationale as an exploration of the strange and disturbing.

Yet having a common ancestry means that classical fine craft and modern art are bound to be in a state of perpetual confusion. Many people – including art professionals – approach modern contemporary artworks in exactly the same way they would standalone classical objects, judging them in terms of their aesthetic, sensorial value, and invariably concluding that the works are seriously deficient in all respects. They might then be prepared to look for a suitable scholarly interpretation of the work – an intellectual justification – but in the light of the self-evident magnificence of classical museum pieces, this grubbing for sloppy seconds can feel slightly condescending, perhaps even demeaning, in that it involves excusing what appears to be adolescent silliness and ineptitude for no good reason, and, worse still, pretending that “bad is good” in willful defiance of the evidence.

As a consequence, much modern art criticism and interpretation is haunted – tormented – by the possibility that the pundits don’t really know what they are talking about, and that they may unwittingly be making colossal fools of themselves. This puts the critics and commentators in a difficult position. Negotiating a safe passage becomes very tricky, requiring surefooted equivocation, and a heavy reliance on circumstantial detail – anecdotal ballast – as the mainstay of any commentary. How else do you write about something when you have no real idea what the topic is?

This means that the default position underpinning almost every conception of art, from the moderately informed amateur to the educated professional, is that classical fine art is the real art – top to tail, beginning to end – and that all the rest is merely adolescent experimentation: fun and entertaining on occasion, perhaps, but ultimately really just an aberration that won’t seem to go away.

This is further reinforced by another popular conception so pervasive in everyday thought and speech as likely to be inviolable. It is the idea that any form of sublime crafting – beautiful workmanship, irrespective of the medium it appears in – ought properly to be described as “art”, so as to elevate it above and beyond the slightly grubby world of mere technique, and mere practiced proficiency. We all seem to believe that it’s wrong somehow not to have a numinous realm hovering “above and beyond” mere crafting, and somehow the idea of ‘art’ seems to answer the call for just such a place. So all manifestations of high culture and civilized refinement are, from this perspective, best labelled as ‘art’. In crafting terms, ‘art’ is as high as you can go.

So the essence of the problem with the question “but is it art?” rests on two factors, both pulling in the same direction, and both, in a confusing way, serving to obscure what “art” actually is. We have the implicit idea that “art” is really classical fine art, combined with the need to distinguish sublime crafting from ordinary workmanship, leading us to want to classify everything in terms of some kind of traditional, classical scheme, yet the whole thing falls to pieces when we are confronted by examples of modern contemporary art, in that works like readymades and found objects and installations bear no relation to classicism.

But if we understand that the category of “art” is itself quite different from “classical crafting”, and that it is based in an immersive theatricality, where artworks are not meant to be standalone examples of fine workmanship, but rather parts of an imaginative landscape – an experiential world – which the artist is inviting us to enter. Modern contemporary artworks, from readymades, to installations and performances, make more sense if you see them as concrete instances of a particular landscape that the artist has created, and can lead you into, rather than as objects to be admired for their congruence with tradition and traditional techniques.

So, then, is it art ? If it’s an object which represents an element in a strange and disturbing world created and orchestrated by an artist, then it is. If it’s a standalone item, to be admired solely for its beautiful crafting, then it’s not art or an artwork, it’s only a crafted piece.

On the Whole Question of Wanting to Define “Art”

There isn’t space here to address all the issues raised by our definition of “art”. Our whole drift may well seem extreme, and unbalanced, and improbable, given the very real desire that pervades popular culture to equate “art” with ‘classical fine crafting’. It may also look like a simple case of self-justification, in that we have simply tried to define art according to our own desires, disregarding alternative interpretations. More to the point, if “art” is as we say it is, why is this news to most people, especially the art professionals?

How on earth, then, could “art” equate only with the ‘strange and disturbing’ ? Surely there’s more to art than that? What about all those hundreds of hours spent in class learning how to draw, and perfecting the use of paints, and training the eye? Surely “art” is somewhere in that rich mix, and not in some half-arsed theory about exploring existential darkness?

We will try to justify this whole approach by reducing it to the matter of what we want “art” to do. From this perspective, there are only two real possibilities with art: the quest for “beauty” – in its widest sense – or an exploration, not of its opposite, but rather of the dark side, the mysterious underbelly of everything positive, optimistic and sunny. The quest for beauty has its own logic, and its own trajectory, and it ends, one way or another, in sublime crafting, and in dazzling technique. It is all about educating one’s aesthetic sensibilities and sensitivities towards an ever deepening appreciation of the subtleties of beauty, in its myriad forms.

An exploration of the dark side of existence is something else altogether. It is more about awakening a certain very specific fascination, and then giving it room to express itself. It is about finding a way to explore the strange and disturbing, using various media, and then orchestrating the possibilities that these media offer. The great thing about art is that it offers a safe and enjoyable environment in which to contemplate all kinds of darkness, without having to submit to this negativity in life itself. Art is essentially a theatrical medium, and an entertainment; it is not real life. But like the best in theatre or cinema, it can, for a time, overwhelm you with its power.

So, in the end, if people want “art” to equate with “classical fine craft”, rejecting other possibilities, then no one should stop them. And if people want to treat modern contemporary artworks as puzzles to be decoded, then let them go there too. But the point is that the way we have defined “art” here reveals art to be an immersive, imaginative experience, much more interesting and involving than the fey tedium of sensorial aesthetics. And our definition makes real sense of the work of many key modern contemporary artists in a way not on offer elsewhere.

Jakob Zaaiman is an artist and writer living in London and New York. He works mainly with photographs, and is interested only in the troubling and disconcerting aspects of life which can be discovered within the ordinary.

Tagged with: art, classical fine craft, Damien Hirst, Fat Chair, Joseph Beuys, My Bed, Tracey Emin