Schopenhauer And Coltrane – The Metaphysics Of Atheism Illumines “A Love Supreme” (Jon Avery)

Arthur Schopenhauer, a nineteenth century German philosopher, praised music as the highest art form because it gives us immediate access to the inner life of human existence and the reality behind appearances.

To grasp the “reality behind appearances” is very similar to the goal of much of Hindu and Buddhist philosophy – which Schopenhauer argues is incidental, even though he has the distinction of being one of the first professional western philosophers to study eastern philosophy. In the Kantian philosophy that Schopenhauer appropriated, our senses only present things in terms of inherent forms of perception, such as space and time, while the inherent category of cause and effect in the understanding gives us the form of scientific laws and knowledge of the outer nature of things.

The fine arts, on the other hand, give us a direct intuition of the inner nature of things by releasing us from innate restrictions on our awareness into the contemplation of beautiful objects of art for their own sake.

Contemplation of the Platonic Ideas (ideal forms as the inner nature of things) in the fine arts releases us temporarily from self-consciousness and thus our troubles in which for a short time we lose our individual consciousness in a universal consciousness of the beautiful. Schopenhauer ranks the fine arts in their metaphysical power to do this from architecture and sculpture to painting and literature, and finally to music. However, before turning to a full exposition of this metaphysical power of music, a seeming contradiction between Schopenhauer’s atheism and Coltrane’s theism must be resolved.

Schopenhauer, who was world-famous from 1862 until 1914, was known for his non-theistic account of human existence that viewed all of experience as the objectification of the ever-renewing desire or will to live or to exist. Even though each individual is mortal, the ultimate source of the individual is indestructible. Thus, all individual existence is a fleeting struggle to exist, and each of us seeks temporary solace or salvation in the satisfaction of our desires.

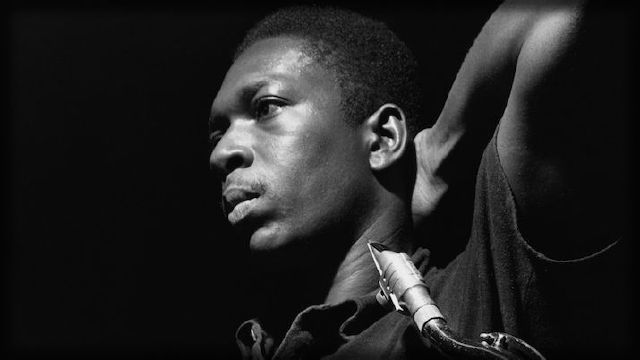

John Coltrane was involved after 1957 until his death in 1967 with “spiritual” jazz. God had saved him from a heroin and alcohol addiction, he claimed, and his music since then had been a praise of the same Deity. For example, in his prayer accompanying A Love Supreme Coltrane wrote, “let us sing all songs to God” and “thank you God”. But his idea of God is not always traditional as in “All paths lead to God” and “Elation Elegance Exaltation” and “All from God” in this same prayer.

Philosophically speaking, how is this seeming conflict between Schopenhauer’s atheism and Coltrane’s theism to be reconciled? Through the fundamental experience of serenity or tranquility and the experience of God’s grace and bliss, which functions in a similar way even though the outward expression is different and even contradictory.

There are four movements to the first Coltrane jazz suite of thirty two minutes and ten seconds called A Love Supreme: acknowledgement, resolution, pursuance, and psalm. The famous four-note-theme or motif of the first movement (F, A-flat, F, B-flat) has the same number of the syllables of both the title of the suite and the first two movements, which provides a rhythmic mantra for the contemplation of God in the rest of the piece. This is seemingly incidental but the division into four parts is significant in Schopenhauer’s metaphysics too, because the world for him has four dimensions and two levels: minerals, plants, animals, and human beings, which exist on the level of objectifications or appearances of desire or the will-to-live as their deeper level and source.

Coltrane even locates the ultimate unifying or spiritual power of music in vibrations: “Thought waves – Heat waves – All vibrations – All paths lead to God.” (Prayer, 3). Schopenhauer accepted in 1843 in his World As Will And Representation that there was a scientific consensus that “all harmony of tones rests on the coincidence of vibrations.”(II, 117)

The material manifestation of the love of God in the four musicians themselves fits this pattern: drums, bass, piano, and saxophone as do the 1, 3, 5, 7 of the jazz chord. Furthermore, it is easy to see the four parts of musical harmony—bass, tenor, alto, and soprano—as another instance in which music and metaphysics collide, for the bass (the mineral realm) provides the foundation, the soprano (the human realm) provides the melody, while the other two voices of the tenor and alto (plants and animals) provide support (or the ripieno) in the rich combinations of the mid-range of this hierarchy of vibrations.

Schopenhauer is so impressed by the metaphysical aspect of music that he writes, “we could just as well call the world embodied music as embodied will.”

Strikingly, though, this unity or harmony of all things is direct or immediate in music, while the understanding of the world in metaphysics is indirect through concepts and Ideas. That is, the will-to-live or will-to-be, which is the source of all things, is communicated immediately in music, but is mediated in philosophy. This concrete immediacy can be felt in the joyful awakening to God in the first movement; the courageous resolution to become a better person in the second movement, the passion of pursuing the way of God in the third movement, and the gratefulness of the purifying rite of jazz improvisation in the final movement.

The spiritual power of music–which must be experienced first-hand to be truly understood–lies in its ability to give us direct access to the inner meaning of life and existence and thus to inner emotional transformation. “This close relation that music has to the true nature of all things can also explain the fact that, when music suitable to any scene, action, event, or environment is played, it seems to disclose to us its most secret meaning, and appears to be the most accurate commentary on it.”(I, 262)

For example, great music captures the meaning of the narrative of a movie in a more forceful way than the plot and sequence of events themselves. Consider the fanfare from Strauss’ Thus Spake Zarathustra in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey as it captures the dawn of humanity or the heart-pounding theme of Jaws when the shark is about to eat a swimmer. All of this is accomplished without words.

Similarly, the sudden breakthrough of realization in the first movement of Acknowledgement and the serenity of the last movement Psalm capture the inner essence of spiritual enlightenment and ecstasy. The frenetic solos of resolution and the frenzied solos of pursuance parallel the inner struggle to shed sins and acquire virtues in the spiritual life of almost any of the religious and philosophical traditions of the world. Thus, the flow of the four movements in A Love Supreme runs parallel to a spiritual transformation in four stages from realization through purgation and finally to purification and bliss or ecstasy.

However, musical experience, like any other mystical experience, cannot be put into words, since purely instrumental music is non-verbal. The composer and the improviser work with elements of melody, rhythm, and harmony to express the unspeakable depths of the emotional life in a safe and hopefully cathartic manner. According to Schopenhauer, “the inexpressible depth of all music, by virtue of which it floats past us as a paradise quite familiar and yet eternally remote, and is so easy to understand and yet so inexplicable, is due to the fact that it reproduces all the emotions of our innermost being, but entirely without reality and remote from its pain.”(I, 264)

Coltrane improvises a melody within the key of F minor by alternating the rhythm, the order of tones, and articulations, all of which captures the inner nature of the emotional life from guilt to emotional relief, and from sorrow to joy. As Schopenhauer writes, “the composer reveals the innermost nature of the world” (I, 260), and this is done by freely combining musical elements with emotional states, which is very similar to the way Coltrane goes about his improvisation.

This tension and release in the emotional or spiritual life coincides for Schopenhauer in the alternation between “discord and reconciliation” in music. “Music consists generally in a constant succession of chords more or less disquieting, i.e., of chords exciting desire, with chords more or less quieting and satisfying; just as the life of the heart (the will) is a constant succession of greater or lesser disquietude through desire or fear with composure in degrees just as varied.”(II, 456)

The satisfactions and disappointments of life are re-created in music by such techniques as subito attacks and crescendos, and of course, the rise and fall of pitch in the melodic line. All of these techniques are evident in A Love Supreme as is the purging of negative emotions such as sadness, fear, guilt, and anxiety so that we can feel joy, courage, relief and peace. Coltrane said as much in a final interview in 1966: “If one of my friends is ill, I’d like to play a certain song, and he’ll be cured.”

Listening to or playing jazz music is a safe way to purge or release negative emotions and to begin a process of emotional rejuvenation, which constitutes the purifying or elevating power of music. In addition, the appreciation of A Love Supreme can be facilitated by the assistance of the titles and prayers written by John Coltrane to accompany his music.

For Coltrane, the underlying unity of all things comes from God’s creative love, but for Schopenhauer it comes from the will-to-live or the unquenchable desire for existence. Today post-modernists would say there is no longer any “grand narrative” or underlying unity to all things. But the orderliness of nature and the direct revelation and transformation of the emotions in music repudiate that view.

There is intrinsic meaning in the endless struggle for life and a higher quality of it. Thus, there is a live philosophical option today between viewing the unity of things in God creative power or the will-to-live. God’s creative power and the urge of desire seem contradictory, but both function to satisfy the human need for metaphysics. Is the foundation of the world God or Desire?

Some scientific pragmatists would even counter that a third option has been missed, namely, quanta of energy. Schopenhauer would retort that energy is the external objectification or appearance of something even more basic, namely the will-to-exist.

Since there is no agreed upon method for conclusively settling the issue for all concerned, it becomes a question of conditioning and disposition. Each metaphysical system thus makes sense of existence and functions to provide a world-view for the theist Coltrane and the atheist Schopenhauer, and can only be evaluated by how well it provides guidance and fulfillment for them.

Music for Schopenhauer expresses the reality behind the world of experience, for music expresses the “true nature of things.” For Schopenhauer, who played the flute for one to two hours a day, music helped him realize on the emotional level what he had understood on the intellectual level about existence.

Similarly, Coltrane’s understanding of God’s love breaks through in the illuminating joy of the opening notes in E major (B, E, F-sharp-B) before moving to the F minor mantra (F, A-flat, F, B-flat) of the first movement in his acknowledgement of God as the source of existence. The difficulty of living simply and shedding sins can be sensed in the second movement of Resolution in the frenetic tension and release of the melodic lines.

The skill of improvising beautiful solos that can be heard in the driving solos of the third movement Pursuance can only come from a deep understanding of human existence and reality. Finally, in the fourth movement there is a revelation of the inner peace of a life successfully lived with either the world-view of the pursuit of the God of love or the reduction of excessive desires.

In short, the metaphysical systems of theism and atheism function to describe the ultimate experience of either attaining the peace of God or the satisfaction of minimal desires. But one is not true and the other false. They are simply different interpretations of the meaning of existence, depending on one’s conditioning and disposition.

Why is A Love Supreme sometimes referred to as spiritual music? Spiritual music has the purpose of expressing the source of existence.

First, there is a happy metaphysical coincidence in the pulse or beat of the human heart and the pulse or beat of a piece of music. This helps tune the soul to the ground of being. Second, meditation is a form of concentrating awareness on the source of existence and Schopenhauer practiced the contemplation of reality, the flute and compassion for all life forms (especially dogs) with the goal of reducing his excessive desires and achieving peace.

The poly-rhythms and rapid improvisations of A Love Supreme require an intense devotion that is not exceeded by even the most fervent monk or nun of any of the world’s religious orders. Yet the most spiritual aspect of jazz music is improvisation – because improvisation is the free and spontaneous creation of a work of beauty. God and beauty are one for Coltrane. And the power to create is shared by God and musicians who improvise. Finally, since beauty is the longstanding subject of the arts, and especially music for Schopenhauer, and it is common for theists to refer to nature as the “beauties of God’s creation,” it follows that jazz improvisation is a spiritual practice.

You can close your eyes and imagine one man strenuously working out his salvation through a horn by reaching for direct and immediate access to the heart of all things. With trance-inducing repetitions of a four note mantra and alternating moods of sadness and joy in minor and major keys, he finds relief at last from the daily struggles of life. The power of transcendental music — with love behind it — to cure souls of the blues, constitutes the spiritual power of A Love Supreme.

Jon Avery Ph.D. is a retired lecturer in philosophy at Bluegrass Community and Technical College in Lexington, Kentucky as well as a musician.

Tagged with: Arthur Schopenhauer, atheism, jazz, John Coltrane, music theory, prayer, spirituality