Perennialism and Primitivism In Psychedelic Religions, Part 2 (Roger Green)

The following is the second of a three-part series. The first installment can be found here.

The following is the second of a three-part series. The first installment can be found here.

An economic approach that more astutely tracks what’s at stake in emergent ayahuasca religions might combine Luis León’s idea of ‘religious poetics’ with anthropologist, Michael Taussig’s ficto-criticism of Latin American economies. I cite these two thinkers to highlight that the very category of ‘religion’ must be contextualized historically within the process of its own making so that we may be able to examine the motivations at stake in recognizing and pleading for recognition of a new religious movement (NRM) as such.

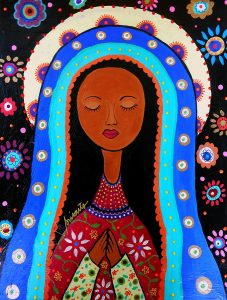

León’s La Llorona’s Children: Religion, Life and Death in the U.S.-Mexican Borderlands advances the idea of a religious poetics that “provides an alternative mode of knowing based on knowledges of the body, which, if not posing a direct threat to modern forms of knowing, competes with them for authority.” (248) Drawing on a blend of ethnography and theoretical discourse, León proposes what he calls a borderlands reading of La Virgen de Guadalupe as a transgressive, border-crossing goddess in her own right, a mestiza deity who displaces Jesus and God for believers on both sides of the border.

His discussion of curanderismo shows how this indigenous religious practice links cognition and sensation in a fresh and powerful technology of the body—one where sensual, erotic, and sexualized ways of knowing emphasize personal and communal healing. La Llorona’s Children begins with a narrative of postcolonial history drawing on Catholic colonization and indigenous deities, arguing that the “borderlands is not only a physical place but also a poetic device for describing perennially emergent and multiplex individual, social, and cultural formations.”(57)

León argues that devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe “is a border tradition, straddling and blurring lines of religious demarcation.”(63) Guadalupe “functions as a transnational symbol, one that is re-imagined in socio-political-spiritual movements; La Virgin de Guadalupe is the fulcrum on which religious poetics in Mexican-American Catholicism pivots.”(93-4) Although León’s work focuses on the borderlands between the U.S. and Mexico, his emphasis on Guadalupe is supported by attention to the persistence of the indigenous Aztec goddess, Tonantzin. In doing so, León’s work exists in a larger movement of Indigenismo prevalent throughout Latin America, but one should not take his descriptive claims about transnationalism to be celebratory claims about “new impulses” in religious diaspora.

Tracking Indigenismo instead requires a re-evaluation of the static and transcendent category of ‘religion’ that had its hold in Religious Studies for much of the twentieth century and a careful navigation of outdated and ethnocentric analytics within Religious Studies discourse. In doing so, both León and Taussig tend to emphasize materialist critiques while drawing on twentieth-century Critical Theory. Bland critiques of consumerism and capitalist economic models such as Stark and Bainbridge’s forget that materialism is both destructive and creative.

It is true that crass consumerism may feel empty and alienating, and that what Herbert Marcuse long ago named “one-dimensional society” has proved to be a threat to liberalism itself. Neo-liberal models, as I have characterized Stark above, set themselves up as critical methods that work transnationally but that remain unaware of the cultural context that produces sociological models based on Western liberal economic and business metaphors of exchange.

In this sense they downplay their ideological bases while naturalizing globalization as inevitable. Anthropology as a discipline has a much richer historical engagement with the idea of exchange, at least going back to Marcel Mauss’s The Gift, which has more recently been taken up in the political-theological excursions of Giorgio Agamben with respect to Christianity.

Anthropologist and aesthete Michael Taussig, by way of an engagement with postmodern aesthetics, has taken a unique path with respect to economic exchange. Taussig has argued in his Beauty and the Beast that the basic human ability to change “nature” structures consciousness and reality through “enchantment” or “magic,” particularly with regard to a variety of indigenous “spiritual” practices (including drinking ayahuasca), but also with respect to plastic surgery fads and paramilitary groups in South America, calling it “cosmic surgery” (instead of cosmetic surgery).

The excessive fascination with the limits of the body that Taussig documents – i.e., drug-lords who wipe their asses with toilet paper that has their initials imprinted in gold on each piece – the postcolonial economic situation in Latin America produces extreme aesthetics that perform an attempt to use technology to merge with nature. This is simultaneously a desperate attempt to spiritually produce the divine through excessive signification. Like León, the emphasis relies on poetic analysis. In his earlier work, The Magic of the State, Taussig gives a striking account of this with regard to metaphor, ritual performance, and spirit possession:

Metaphor is, in other words, essential to the artwork by which the sense of the literal is created and power captured. As to the nature of this artwork, the great wheel of meaning is here not only state-based but based on an artistic death in which metaphor auto-destructs giving birth to literality whose realness achieves its emphatic force through being thus haunted. The real is the corpse of figuration for which body-ritual as in spirit-possession is the perfect statement, providing that curious sense of the concrete that figure and metaphor need – while simultaneously perturbing that sense with one of performance and make-believe in the “theatre of literalization.”(186)

Taussig’s language is difficult to succinctly explain. While drawing on Georges Bataille’s notions of “excess”, he both draws on and self-consciously critiques Euro-centric discourse in a method he calls ficto-criticism, which blends ethnographic participant observation with extreme self-awareness in documenting human behavior. His materialist focus draws on a tradition of Marxian criticism that corresponds to the economic situations in Latin America while also attending to forms of magic that exceed the discourse of liberation theology.

It is Taussig’s economic focus, combined with León’s Indigenismo and religious poetics, that I argue are helpful for analyzing psychedelic and ayahuasca religions as NRMs. In order to demonstrate this, the second half of this paper will focus more directly on ayahuasca religions in Brazil. I will then conclude with some brief thoughts about the transnational diaspora of these religions.

Ayahuasca Religions

Among the twentieth-century hybrid religions that employ ayahuasca as a sacrament, Santo Daime is the first. As Marcelo Mercante summarizes:

Since the 1930s, three syncretic, Christian-based, and organized movements have evolved using the beverage as a sacrament. The first of these was the Santo Daime movement, founded during the 1930s by Raimundo Irineu Serra, called Mestre Irineu. The Barquinha movement emerged during the 1940s headed by Daniel Pereira de Mattos, known as Frei Daniel. And in 1960 the União do Vegetal movement, which was started by José Gabriel da Costa, the Mestre Gabriel.(13)

As Mercante tracks the history, “Until 1890, Brazilian Christianity had been characterized primarily by lay organizations lead by charismatic leaders and by various brotherhoods.”(54) The internal difficulties of traditional orders made it easy for African, Indigenous, and Christian religions to fuse, along with “brotherhoods” and collectives such as the Masons. Capelinhas de Estrada, or “road-chapels” sprang up in resistance to Roman Catholic reform movements gathering force in the 1890s.(55) It is likely that this is how Raimundo Irineu Serra came to encounter ayahuasca, or yagé.

In The Religion of Ayahuasca: The Teachings of the Church of Santo Daime, Alex Polari de Alverga boldly claims: “Christ is risen among us in a new form! He left the sumptuous cathedrals and now He pulses in the heart of the Amazon forest. The Green Hell of the conquistadores has become the Green Paradise for those willing to enact the conquest of themselves. The forest is the Garden of Eden, wherein may be found both the Tree of Life and the forbidden fruit.(2)

Polari de Alverga studied under Padrinho Sebastião Mota de Melo, who took over leadership of the church in the early 1970s after Mestre Irineu passed away. He writes, “Orthodoxy, heresies, the Inquisition, the genocide of pre-Columbian people, all of this darkens and clouds the water of the spring, the clear and pure fountain that is Christ himself. But I had the blessing of seeing this through Daime.”(12) Although he is aware of this difficult history, Polari’s religious experience clearly draws on primitivist ideas. Jonathan Goldman, in his preface to Polari’s book, notes the use of both the six-pointed star and the two-beamed cross in Santo Daime. This Santo Daime Cross sells for $500 on indiegogo.com

As Goldman writes, “the lower crossbeam, which it shares with other Christian Religions as well as with many ancient peoples, symbolizes the first part of the mission of Jesus, which was to plant the seed of compassion in humanity and to call us to direct, conscious connection to the divine.” Goldman characterizes the Daime religion’s use of the star as “the uniting of these symbols within a single religion, and the subsequent act of singing and dancing around them, symbolically reunites Christians and Jews.”(25)

Although the common parlance in religious studies scholarship is to emphasized “hybridity” within NRMs, the advocates of ayahuasca religions often use the term ‘synchronic’ wholeheartedly. This emphasizes theological roots in nineteenth-century European Spiritism and New Thought movements. The esotericism of Allan Kardec and Emanuel Swedenborg often show up in the literature as well. These tendencies allow the religions to move quite easily in a globalized diaspora.

Another constantly recurring reference in the literature is the 20th century English writer, Aldous Huxley. Huxley remains one of the primary theorists of the psychedelic experience more than half a century after his death. Huxley believed that psychedelics offer the possibility of democratizing mystical experience for those who would otherwise not have the patience or dedication to commit to hours of prayer or mediation. He believed they gave common people the ability to glimpse into the ways great visionaries throughout history saw.

Oftentimes in psychedelic literature, psychedelics are associated with an ongoing scholarly quest to find the “original” oblation of the Soma sacrifice as described in the Rig Veda. This scholarly discussion, which Huxley participated in, is ultimately rooted in nineteenth-century philology and euhemerist mythology that theorizes Religion as a transcendent human category that aligns with social-Darwinist readings of the “evolution” of human civilization.

“Soma” appears as a mass-controlling, experience-numbing drug in Huxley’s Brave New World, but after Huxley experienced mescaline and LSD in the 1950s, after years of involvement with American Vedanta, he came to see certain drugs as potentially beneficial to society. His last novel, Island, as well as his late 1950s essay, Brave New World Revisited, revised many notions present in his early work. Polari de Alverga appears to be directly influenced by Huxley in statements such as: “The Daime has the power to take shortcuts on the road that leads to a direct perception of God in ourselves, immersing our minds in a state without intellect where the miração [vision] imposes itself and silences us.”(33)

With respect to ayahuasca’s relationship to the “original soma,” Polari writes:

Could it be that Daime is the same Soma reappeared at the twilight of the gods, at the moment when Siegfried played the trumpets ending the old Nordic and Arian mythologies and inaugurating a new era of Juramidam, the Divine Being that inhabits the telluric forests of the new world? What does it matter in what form or class of being the Divine Avatars manifest to man and woman? Did Vishnu not come as a turtle, fish, and bird? The Logos, the Divine Verb manifested, adopted Christ in a human form, so why not a plant?(31)

The transcendent perennialism present in this theological apology is seen as old fashioned and disdained among many contemporary scholars of religion. It is associated with early writers in the field such as Huston Smith and Mircea Eliade. It is also seen as deeply unethical from the perspective of post-colonial theory and its derivatives, especially among Native Americans who may even view it as perpetuating a longstanding genocide against indigenous peoples in the Americas. Because of these analytical problems, scholars working on new religious movements must constantly navigate between varying attitudes of suspicion from people belonging to ayahuasca-using religious communities, scholarly peers, and over a generation of public discourse vilifying all drug use.

In scholarly terms, the theological primitivism and perennialism present in Polari and other psychedelic religious enthusiasts risks what academics call a ‘post-race attitude,’ which emphasizes both social progress and ahistorical, transcendent categories that obscure persistent inequities. The same attitude is present in scholars of religion like Bainbridge and Stark who present a “secular” neutral zone as a frame for scholarly research.

In contrast, sociologist of religion, Antony Alumkal writes, “A racial project in a congregation […] would consist of an interpretation of race held by one or more members of the congregation and the manner in which this interpretation is manifest in practice.”(153) Obtaining such information from members of ayahuasca religions can be tricky, especially if members adopt Polari’s perennialism and the idea that ingestion of entheogens give one access to culturally transcendent experiences.

Alumkal builds on Ammerman, et al.’s scholarship to build a framework, including a congregation’s “ecology” in terms of demography, culture, and organization. While demography might be difficult to obtain through self-identification of church members, the cultural category becomes much more crucial. As Alumkal states, “Regarding the cultural layer, a researcher would want to understand patterns of race relations in the greater community, as well as the particular ways in which the racial groups found within congregations are racially constructed by members of the greater community.”(156)

American scholars must, however, understand that racial division and discourse in Latin America does not work in the same ways as the United States. “Whiteness” is indicative of social class but may not correspond to skin tone, which gets emphasized in social politics in the U.S. When it comes to organization, Alumkal suggests that race be understood “alongside such things as worship styles, small group ministries, and doctrinal emphases as a form of specialization.”(157)

Although Alumkal’s work here focuses on Asian American experiences, his point that concepts such as “congregationalism” and the effects “larger religion tradition or subculture” on a group’s self-understanding are important for understanding the complexities of culturally mixed and multiethnic religious movements such as ayahuasca religions: “for a racial minority Christian congregation, racial projects may be derived from those of a predominantly white Christian subculture. However, the members of the congregation may engage in a process of reinterpretation – or “rearticulation” to use Omi and Winant’s term – as they adapt racial projects to their own interests and context.”(159)

Alumkal notes how white Evangelicals often present a racially transcendent discourse that asks congregants to “overcome racial divisions.” Yet such rhetoric has an altogether different meaning among marginalized groups: “In contrast to whites, Asian Americans who employ the ‘all are one in Christ’ rhetoric are responding to their problematic racial identity as ‘model minorities’ and ‘perpetual foreigners,’ and thus infuse racial reconciliation theology with a new set of meanings relevant to their own context.”(159) Alumkal’s more nuanced view of issues related to race and ethnicity (“racial formation theory”) and Nancy Ammerman, et al.’s focus on religious congregations would be a productive analytic for addressing ayahuasca relgions so long as one keeps in mind Alumkal’s qualifier that

Researchers who wish to apply this framework to another racial minority group should be aware of the ways in which the racial experiences of Asian Americans may differ from those of other groups. Researchers wishing to apply this framework to predominantly white congregations should address the ways in which white privilege shapes congregational life.

As noted with respect to Euro-American influences on ayahuasca religious theology, any study of ayahuasca maintains a complex negotiation between ongoing hybridization and colonization, especially among economically dominant rhetorics popular in New Age and neo-shamanic discourses, which often display ethical problems related to white appropriation.

Moreover, the complexities with respect to race, ethnicity, and racial construction in Amazonian contexts are not the same when ayahuasca religion’s move transnationally to places like the United States. They are therefore potentially host to many projections and especially romantic assumptions about “otherness.” The use of entheogens only exacerbates this because of the conflation between entheogens as sacrament and enculturated fears about drug use and its association with social deviance.

While Alex Polari de Alverga’s The Religion of Ayahuasca displays many of the esoteric and New Age themes present in a dominant Euro-American presentation of the NRM, Marcelo Mercante’s dissertation, Images of Healing, presents a much more nuanced – though not altogether unproblematic – view of the Barquinha religious system. Mercante’s revised dissertation, which he wrote for a doctorate in Human Sciences at Saybrook University under psychologist, Stanley Krippner, who has been a major voice in the study of altered states of consciousness, emphasizes the ceremonial aspects of the religion.(3)

Mercante importantly characterizes Barquinha as a branch of Santo Daime, and his scholarly approach, though methodologically problematic to some, offers much more for researchers than the more evangelical and apologetic claims present in Polari de Alverga’s book. At the time of his research, Mercante tracked a congregation of 119 members, along with leaders such as Madrinha Chica, who now have an emergent presence internationally via YouTube.

There is a serious risk of reification of Christianity here. In the Center’s cosmology Jesus Christ does occupy its core. However, the cosmos is larger than the one presented by Christianity, a result of adoption of practices and symbols from other cultural matrixes. More than a mere transposition of those non-Christian practices into a Christian universe, which would mean a transformation of those practices, the Center welcomes Jesus into the non-Christian universe, merging both, enfolding a Christian ethic into a previously pagan universe. Old practices are kept, but now they are guided by love, by charity, by humbleness; they are no longer supposed by selfish motives.(96)

Such a statement is tremendously loaded, even if I accept Mercante’s scholarly attempt to be as clear as possible. Mercante notes that he himself was a part of the congregation before entering his doctoral research and that even when he returned and was granted the approval by church leaders to conduct his research, his first priority was to his religious devotion. He notes, “I realized during my first conversations with the Madrinha that there was a standard speech ready to offer for researchers.”(43)

He also states, “The people in the Center have become increasingly concerned about what researches [sic] will do with the material they collect during their visits.”(48) Madrinha Francisca, who leads the Center where Mercante did his field work, and he characterizes her as only having two “influences on her spiritual career: Roman Catholicism and Daniel Pereira de Mattos,” or Frei Daniel.(71) Madrinha Francisca formed a congregation around her home after leaving Santo Daime’s Casa de Oração, feeling the group had gone astray from the founder’s practices.(74)

Frei Daniel first took ayahuasca with Mestre Irineu in 1936 and went on to form the Barquinha branch, or “the Boat,” which developed from is miração (vision of a boat) while taking ayahuasca. From this vision he developed Romarias (pilgrimages) based on a psychedelic spiritual experience in which participants travel out from their physical space into a “spiritual sea” and then return.

Of the 119 members Mercante tracked, 25 had been there for thirteen years. Only 9 had been there less than 5 years, though his data did not include children of members: “The average age of men is 35.62 years old, slightly smaller than the average for women, 36.02 years old.”(80) Only 11 members were over 51 years old, making it a young group. 49 members had not completed high school, 30 had completed high school, 18 had completed undergraduate, 11 were college students, and 5 were retired. In addition to members, many international visitors attended services.

Mercante also notes:

In the local neighborhood, the influence of the Center is diminished by the fact that two other centers of the Barquinha within walking distance from the Center. However, many people visit all these Barquinha’s without any problem. Sometimes they leave a Festa at one of the Barquinhas to go to the Festa at another.(83)

Mercante notes no disapproval among leaders concerning people attending multiple groups, and even though Madrinha Francisca left one group, she did so without animosity and never gave up membership or said she would not return. If there is religious “entrepreneurship” here, it is certainly not the capitalist one to which Stark and Bainbridge adhere.

Roger K. Green is a lecturer in the English department at the Metropolitan State University of Denver, where he teaches literature, rhetoric, and songwriting. He has studied at the School of Criticism & Theory, and his dissertation on political theology and psychedelic aesthetics explored transatlantic influence of Aldous Huxley, Antonin Artaud, and Herbert Marcuse in literature. He is a former guitarist of the rock band, The Czars (John Grant, Bella Union, UK) and continues to perform and produce music. He is currently completing coursework for a second PhD in Religious Studies and Theology at University of Denver.

Tagged with: Anthony Alumkal, Ayahuasca religions, drugs, entheogens, indigenismo, LSD, Luis Leon, Marcelo Mercante, Michael Taussig, New Religious Movements